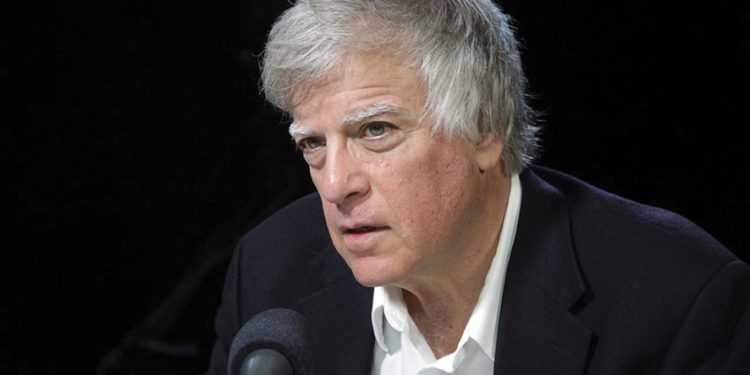

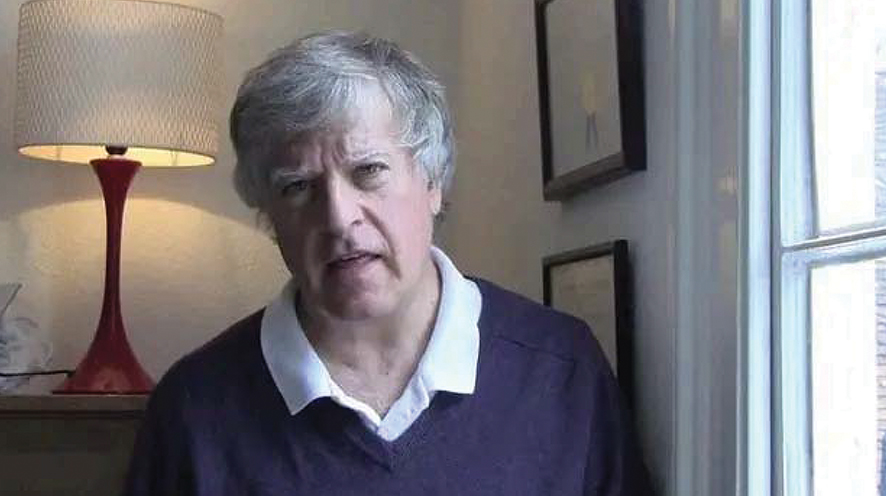

American journalist and historian David Satter is the author of numerous books about the collapse of the Soviet Union and Russia (Age of Delirium: The Decline and Fall of the Soviet Union; Darkness at Dawn: The Rise of the Russian Criminal State; It Was a Long Time Ago and It Never Happened Anyway: Russia and the Communist Past; Never Speak to Strangers and Other Writing from Russia and the Soviet Union). A correspondent for the Financial Times and one of the first journalists to investigate the involvement of Russian special services in the Moscow apartment bombings at the beginning of Putin’s rule, he was expelled from Russia in 2013.

RFE/RL’s Georgian Service met with Satter to discuss the Russia-Ukraine war and the new dynamics of Georgia-Russia relations. We kicked off the conversation by asking about the Russian people and their sense of responsibility for all that’s happening in Ukraine.

“Those signing up are signing up in some cases because they feel they have little alternative to support their families and themselves,” Satter says. “The Russian people don’t understand, for historical reasons, the importance of respecting the rights of others. They were victims of the Soviet regime, without a doubt, but they also supported that regime, because Russia has a messianic mentality. Russia has the mentality of a movement, not of a state, not of a normal country. In a movement, the individual doesn’t matter; people take their sense of individual self-worth from their participation in the movement, and it’s difficult for them to break with that movement, because this is how the psychology of the country has been distorted. Under other conditions, Russians could behave very differently, and one of the ways to create those other conditions is for Russia to be defeated in this war.”

Do you have any examples where, in Russian history, they behaved differently?

The serfs were freed after the Crimean War. After the Russo-Japanese War, Russia got a constitution for the first time. And the defeat in the Cold War, if we want to speak about that, at least gave the possibility of putting an end to communist ideology, if not communist practices.

But isn’t that all domestic? What I meant was the respect of borders and other nations.

No. That has never been. The fact that many, many Russians and other people were victims of the Soviet regime doesn’t mean that every aspect of their psychology was healthy. Far from it. Russia is in many ways a sick country, and it’s sick because of what was done to the Russian people historically. They were slaves. And then, after a brief period, they were enslaved a second time by the communist regime. This had a terrible effect on people’s personal lives, on their psychology. I’ll give you a simple example: After the fall of the Soviet Union, Russians became obsessed with sports. When it appeared that Russia was no longer a great power, people expressed their desire for victory, for glory, for collective action, by rooting for the Russian sports teams. And they became really obsessed with this. If there was a Russian victory, everyone on the bus was elated. After all these years of oppression, in which people did suffer, and in which many Russians behaved very nobly, but the majority did not, they’ve become psychologically conditioned to think in terms of participating in some great crusade, and deriving a sense of self-worth from being part of this crusade. I mean, the average Soviet citizen was not a citizen: he was a builder of communism.

This mentality definitely always existed. And the economic transformation of Russia after the fall of communism did not change it, because there was no underlying change in the attitude toward the individual. And when Putin needed to use this mentality to save him and his corrupt circle, that mentality was there. It just had to be mobilized. It hadn’t changed.

In an essay of yours you underline an outlandish statement from Putin that 99% of Russians would be willing to sacrifice their lives for their country. What do you think the actual number is?

I don’t think any Russian really wants to sacrifice their life, but they are certainly ready to, and they accept this eventuality if it happens. I think the percentage of those we see fighting in Ukraine, the wave upon wave signing up and nobody stopping to think about the senselessness of it – compared to Western society, that percentage is pretty high.

So when a Russian soldier is sent into that meat grinder, as per the military term, are they dying heroically, or do they have such a slavish mentality that they simply cannot disobey orders?

They can’t imagine disobeying orders, but they are also convinced that this is heroism. They’re propagandized, and everyone else thinks likewise; very few of them have the strength to think for themselves, because it’s the mentality of a movement, especially so in conditions of warfare.

What impact does that mentality have on non-Russians, especially when it comes to the neighbors, such as Georgia?

There’s a potential for herd mentality everywhere, including the United States. The difference is that, for example, in the US, there are democratic institutions which keep these movements under control. In Russia, the country is the movement.

But in Georgia, even in Soviet times, maybe because of Georgian traditions, maybe because of the kind of country Georgia is, we have always seen people striving for independence, and displaying more skepticism than we see in Russia. But that doesn’t mean that in the right conditions, that kind of mentality cannot be fostered in Georgia. It can be, up to a point, but not to the degree that it is in Russia.

What impact will the eventual outcome of the Ukraine war have on Georgia?

Well, if Russia wins, the demands on Georgia will intensify, of course. There will be no political independence for Georgia, and there could be further occupation. If Russia loses, it’s a completely different situation. Georgia will have the chance to recover its occupied territories.

Those are two maximalist scenarios, where Russia outright loses or outright wins. Let’s also consider a frozen conflict or some sort of shaky ceasefire where nobody claims victory.

In that case, where Russia does not come out of it a triumphant conqueror ready for the next conquest, it would at least give Georgia some breathing space.

Ahead of Georgia’s elections, the ruling party said we should “apologize to our brothers in South Ossetia and Abkhazia,” try to work on reintegration, and that it goes hand in hand with having good relations with Russia. What would that look like if it ever came to fruition?

Well, it would be total subordination. There would be a Belarus-type governance. In that case, if Russia were victorious in Ukraine, and if Georgia tries to repair its relations with Russia, it will be strictly on Russia’s terms. There will be the appearance of national independence for Georgia, but not the reality.

And the reintegration or reunification of Georgia?

Not if Russia wins in Ukraine.

Can one haggle out those regions with Russia by trying to cozy up to them?

No, no, no, no. They aren’t interested in negotiating; they’re interested in domination. By holding on to those regions, they have their foot on Georgia’s throat. They don’t want Georgia to have the conditions to be able to assert its full independence.

What if Georgia turns itself into a Belarus-like entity? Could the occupied regions be given as a reward for loyal service?

No. Russia doesn’t give out rewards. We know this. They have no motivation to do so. If you already turned yourself into a vasal, why should Russia reward you? This is a movement with a mission, and giving rewards to those it dominates is not part of that mission.

Interview by Vazha Tavberidze