In this harrowing landscape, Médée emerges as a prisoner of circumstance, her character a symbol of resilience in the face of overwhelming adversity. As she navigates the confines of her fate, the music becomes a cathartic force, expressing the tumultuous emotions that surge within her tortured soul. The arias, charged with anguish and defiance, resonate with the universal struggles of those trapped on the fringes of society.

The opera’s poignancy lies in its ability to transcend the confines of time and space, drawing parallels between the ancient myth and the contemporary crises that echo through the corridors of our world today. Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s composition, reimagined against the backdrop of modern strife, becomes a powerful testament to the enduring relevance of opera as a medium for exploring the depths of human experience.

As the final notes reverberate through the auditorium, “Médée” leaves an indelible mark, imploring its audience to confront the realities of displacement, imprisonment, and the indomitable spirit that persists even in the bleakest of circumstances. This production is not merely an opera; it is a poignant reflection of the human condition, a stark reminder that, in the face of adversity, the transformative power of art endures.

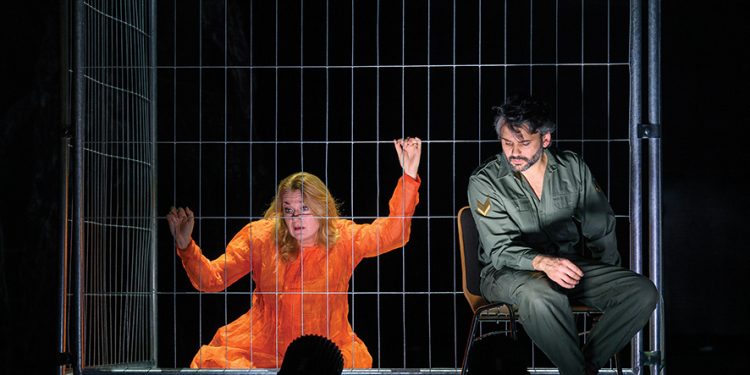

The whole impression is, however, quite taken down by the production by Peter Sellars, whose attempt to take the action into a contemporary refugee camp ambience appears too far fetched and thus misses the point. Additionally, the aesthetics, reminiscent of a US American prison, are an unhappy choice, with orange prisoner uniforms, menacingly armed guards and a military vehicle having little to do with Médée’s tragedy. The costumes by Camille Assaf don’t add much to the characters or action, delivering looks that lack thorough background concept. Last but not least, the stage settings by world famous architect Frank Gehry with his signature silvery metal structures whimsically installed on the stage and hanged up in cloud formations above evoke the mood of unfinished haphazardness and a hastily constructed experiment of stage design rather than a well-composed setting for a baroque opera.

All of this did little justice to the 300-year-old but still up-to-date music by the French composer Charpentier, one that still speaks to the audience and touches the senses. The impression was only saved by the incredibly impressive performance of the Freiburg Barock Orchestra conducted by Simon Rattle – a genious of a conductor and unforgettable performances of the choir and the singers. Médée interpreted by Magdalena Kozena will go into history as one of the strongest and most vibrant female protagonists, portraying in her voice and acting all the anguish, desire and disillusionment a female character can give. With Reinoud Van Mechelen as Jason expressing in his every movement and tone the whole complexity of a failed lover, basking in malignity and callousness to Médée’s sufferings. Princess Creuse and King Creon, performed by Carolyn Sampson and Luca Tittoto respectively, delivered unforgettable performances, adding to the protagonists’ contemporary humanly traits, and timelessness to Charpentier’s musical masterpiece with all its grandeur and deeply moving melancholic notes.

For the Georgian public, an opera relating to Medea, as she is generally referred to, is of particular interest and importance, because this female character is irrevocably connected to the Georgian cultural subconscious. The Greek myth about the Argonauts in search of the Golden Fleece that was treasured by the King of the Colchis is part of Georgian-Greek archetypal imagery. The Kingdom of the Colchis was situated on the coast of the Black Sea in Western Georgia, and Medea, the King’s daughter was not primarily perceived as a wicked witch and murderer of her kids but a healer, a betrayed lover, an abandoned and desperate mother. Even today, most apothecary shops throughout Georgia use the symbol of Medea with snakes as a sign carrying the message of female powers and magic, while the Golden Fleece, the stolen treasure, is the eternal loss resulting from the cunning trickery of adventurous Argonauts headed by daring Jason – an ambivalent hero. A contemporary reading of this myth from Greek antiquity would however reveal to us the tragedy of a woman whose destiny is decided by men only: her father, Aietes, the King of Colchis who expulses her from the palace for helping the Argonauts; Jason, who leaves her for another woman and puts her in prison, traditional morals and common sense sticking to the male perspective that convicts and demonizes her as a murderess of her own children.

A more substantial alternative to reading this complex female character would probably suggest a closer analysis of the Medea archetype in contemporary societies. Medea as not the wicked witch but the healer, understanding the laws of nature; a woman full of passion and capable of deep emotion, ready for any sacrifice for the sake of love and a desperate mother. It is the military logics and callousness of war rationale of the male characters that lead Medea to the extreme and turn her into the monster that she becomes.

Marc-Antoine Charpentier’s music, dating back to 1693, the year his work was first staged at the Opera in Palais Roayal in Paris, contains all of these deep controversies. Maybe if Médée was staged by a woman director, the production could finally give a female perspective and vision of all the complexities and abysmal passions contained in her character. This, however, remains a question for the future.

Review by Lily Fürstenow-Khositashvili