As the sun waned on the horizon on Monday, July 31, the cries of “sa-kart-vel-o” rang out over the placid shores of Batumi. Slowly pulling away from the port was the hulking mass of the cruise ship Astoria Grande, laden with a legion of Russian tourists. For the second night in a row, the ship had been forced out of port earlier than scheduled by the crowds of Georgians gathering in the area.

According to members of this immense crowd, the cruise ship’s passengers, who were largely Russian citizens, were in favor of the Kremlin’s imperialist agenda and supported their country’s ‘special military operation’ in Ukraine. For some, this went as far as claiming that they were here to infiltrate Georgia and spread pro-Russian sentiments. While this may appear to be common conspiracy theory rambling, when the Russian passengers were allowed to disembark on the first visit, the reality was sobering.

“We don’t know about the occupation. You were a republic of ours, a union and not an occupied country,” one of the disembarking tourists claimed to local reporters. “Russia is not an occupier, what did we do, did we occupy you? We were helping you, we liberated Abkhazia from you. They asked us to. I was in Abkhazia and I saw houses, all of them had broken windows. They were destroyed by you. Russia helped Abkhazia to get rid of you,” the tourist stated, much to the shock of the majority of the nation.

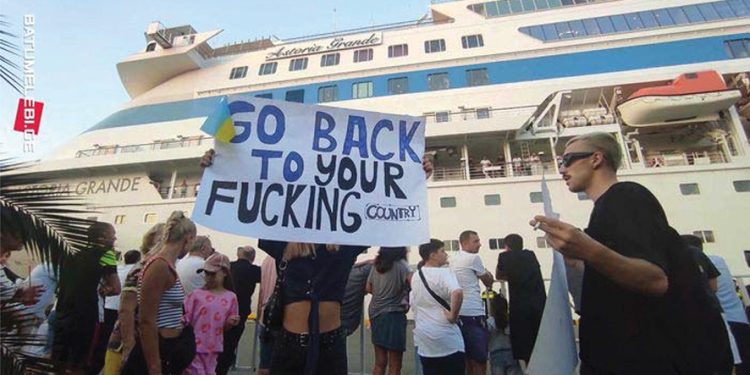

Outraged, many went to social media to sound the call for an increased presence at the port to oppose the presence of the Russians. Groups online quickly coordinated protests, with even students posting a Facebook event to “meet the occupiers,” saying “there is no place for the Russian ship in the port of Georgia.” Armed with signs, flags, and colorful language, the groups converged on Batumi’s port as police scrambled to halt their advance.

While much of the first night went smoothly, there were still tense moments where protesters and police clashed. Indeed, 23 protesters were arrested and removed from the port. Despite this, several Russian tourists landed on Georgian soil to seek out their vacation fantasies, and as they walked off their ship, they found a curious media interest in their takes on the situation. Not willing to accept the humble tourist tradition of avoiding all things political, religious, and otherwise sensitive, they let fly with a volley of controversy.

“We are from Russia, from Novosibirsk. Georgia and Russia are good friends, we rest here, we like Georgia, there are good people here. These are only small groups, Nazis, who want war. Bad people are everywhere, there are no bad nations, there are bad people. No, I don’t think that 20% of Georgia is occupied. Russia has a good attitude towards Georgia. People come here and return with only good impressions,” one said.

“I know Abkhazia, I don’t know the occupied territories. Abkhazia is not Georgia, nor is it Russia. I have been to Abkhazia, I talked to people, I was interested in their opinion, whether we are occupiers or not. They told me, Russians are good people, come, live here, travel. About five years ago, I was last in Abkhazia, on the border,” the same person added, seemingly unphased by the gravity of their words.

Following this statement, along with others made in a similar fashion, Georgians took to social media to decry their presence. One of these is Rusudan Epadze, a communications expert and blogger at youth initiative group 16th Element. “Russia’s escalating influence on Georgia has reached concerning levels, permeating various aspects of Georgian society,” she writes.

Outlining the larger issue, she starts by saying “uncontrolled migration has contributed to an increase in apartment rental prices, rendering them unaffordable for a significant portion of Georgian citizens. The real estate market is also affected, with Russian buyers driving up prices, and with a lack of proper oversight on their acquisitions further exacerbating the issue.”

Epadze adds that along with this influx of Russian citizens, a significant number have started companies in Georgia “preferentially hiring their fellow citizens and evading taxes through informal financial channels.” Indeed, according to a Transparency International report released this month, since the start of the war in Ukraine, Russian citizens have founded 21,326 companies in Georgia, which is three times more than the previous 27-year figure. Most are individual enterprises. “This phenomenon has raised apprehensions due to its potential economic and social ramifications,” Epadze states.

“Adding to the sense of threat is the fact that approximately 20% of Georgian territory remains under Russian occupation, and instances of Russian troops kidnapping Georgian citizens continue to persist with little to no accountability for their actions, including incidents related to bodernization,” she adds.

Rusudan’s statements echo in a more refined way what many of her peers have been writing on social media. Georgian Dream and its supporters have taken to labeling the protesters as racists and xenophobic actors acting “on behalf of the opposition.” Interestingly, this is parallel to the statements made by Russian Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova.

“Inside the country, this action had no support. We receive a large number of appeals from Georgian citizens who say that this boorish provocation is unacceptable for them, that they have nothing to do with it as a country, and who dissociate themselves from it,” Zakharova stated, echoing quips made by Georgian Dream senior leadership. Chairman of the ruling party Irakli Kobakhidze, in his standard coarse and unkempt fashion, called the protesters “boorish” and claimed that their behavior “is what caused the 2008 Russian invasion.”

Despite all of this, the resistance in Batumi held, and ultimately the ship was forced to leave early on both occasions. In the end, the cruise line removed Batumi from their schedule of port stops, though did not officially confirmed the reason for this action. While this is a victory for the protesters and their supporters, it is a sign of the stress being put on the population that has seen an estimated 222,274 people enter Georgia from Russia in that past year. Most sources put the number that stayed in the country around half of that number.

In Tbilisi, these tensions between Russian visitors and their Georgia would-be hosts have come to blows. Video circulating on social media shows young Georgian men and allegedly intoxicated Russians engaging in hand-to-hand combat in the streets of the capital, with some seeming to sustain considerable injuries. However, at the time of writing, there has been no confirmed wounds or arrests in these matters that, according to those posting on social media, stem from the Russian’s comments about Georgia’s status as a former Soviet Union state.

The resistance to this so-called “Russification” of Georgia is unlikely to wane. As the ruling party takes less than admirable steps to placate not only the Kremlin but also the Russians that have made their home here, the Georgian citizenry are quickly going to find themselves in an uncomfortable position. In the words of Georgian President Salome Zurabishvili, “Russia is testing a second front today through ‘soft power,’ through propaganda.”

By Michael Godwin