In the midst of the Ukraine conflict, Western sanctions, and the consequent deterioration in EU-Russia ties, Brussels is attempting to diversify its energy supplies. In December 2022, the presidents of Azerbaijan, Romania, Georgia, and Hungary signed a pact in Bucharest, which was attended by EU Commission President Ursula von der Leyen, to connect the EU with Georgia and Azerbaijan and export green energy from the South Caucasus. The signing ceremony came after an 18-month feasibility study in 2022.

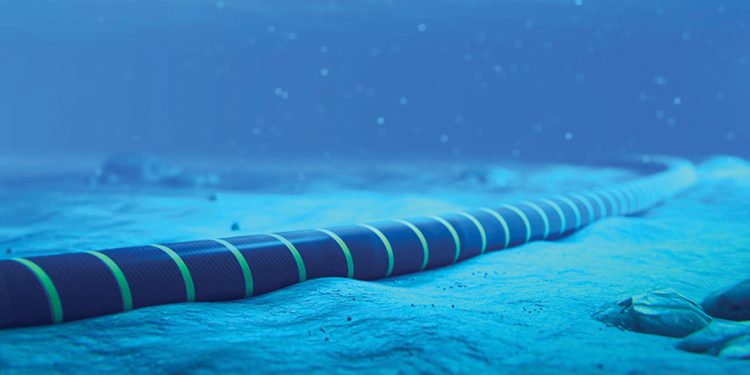

Georgia and Azerbaijan will be able to sell green power to the EU market thanks to the 1,195 km long electricity cable (1100 km undersea and 95 km land). It will also encourage local clean energy development, but more crucially, it will improve the likelihood of EU direct foreign investment in Georgian and Azerbaijani renewable resources. The EU is particularly interested in Georgia since it has a tremendous potential for converting its rich hydro resources into power.

The concept of an underwater power cable had been in the works for quite some time. The project’s initial cost is estimated to be approximately $2.7 billion. The funding will come from international institutions such as the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD). In addition to the power line, a digital data cable is planned, which will assist the South Caucasus to become more connected on the EU internet web market.

The project’s financing is part of the EU’s ambitious Global Gateway plan, a global effort to compete with China’s massive Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), that intends to mobilize more than 300 billion Euros ($318.41 billion) in the coming years. The Black Sea cable project is expected to be operational by 2029.

The EU’s energy interests in the South Caucasus have long been evident, as seen by its financing for a succession of pipelines and railway lines developed during the 1990s that connect the Caspian basin to Turkey and the European market. As additional evidence of the region’s energy importance to the Union, von der Leyen visited Baku in July 2022 and signed a new gas deal aimed at gradual expansion of Caspian gas exports into the EU market over the coming years.

There are no assurances that the project will be realized, as previous trans-Black Sea projects have failed. One example was the failed Liquefied Natural Gas effort between the EU and the South Caucasus. Indeed, the current turbulent political context, particularly the ongoing military conflict at sea, reduces the likelihood of success. Nonetheless, the impetus for the installation of the underwater cable is considerably stronger than it was before 2022, when the EU was heavily reliant on transit through Russia and its energy resources.

The EU’s push toward the Black Sea and the South Caucasus is powered by geopolitical cataclysms such as the war in Ukraine and the changing nature of Eurasian connectivity, which for decades mostly ran through Russia. As the corridor through Russia is stagnating because of the Western sanctions, the likeliest alternative is the so-called South Corridor which connected the Black Sea and Turkey with the Caspian Basin and Central Asia.

Moreover, from a Eurasia-wide perspective, the route could also link the EU and China. Before the war, the Black Sea was a route where 3.8% of global trade transited, as opposed to 17% which went through Russia. But the the end of 2022, the transit through Russia was down by some 40%. Part of it moved to the Middle Corridor. Indeed, cargo shipments along the route grew to 3.2 million tons by the end of 2022.

It is even expected that the Middle Corridor’s capacity could reach a staggering 10 million tons per year. This comes in a striking contrast with the period of 2020-2021, when the throughput was between 350,000 and 530,000 tons. This is why the EU is supporting the development of Black Sea infrastructure.

The war in Ukraine has thus served as a highly impactful geopolitical development, one which is set to change the way the EU and perhaps even the collective West had been viewing the wider Black Sea region since the 1990s. The need to expand into the region, which is increasingly seen as a faultline between Russia and the West, needs to be done not solely through traditional political and military measures, but most of all via economic and large-scale infrastructure projects. Eurasian geopolitics (the expansion of the Middle Corridor) favors this approach, so is the relative Western unity when it comes to Russia’s challenge to the present order.

Analysis by Emil Avdaliani

Emil Avdaliani is a professor of international relations at European University in Tbilisi, Georgia, and a scholar of silk roads.