I’ve lived in Georgia for coming up 16 years. I have three half-Georgian kids here who are growing up within the Georgian state education system. So far, they seem to be doing well. I’m aware they have the advantage of my “Western” influence giving them a tolerant, open, democratic and contemporary outlook on life, one not driven by tradition or religion. Many of the kids I met in Kakheti last week don’t have such an advantage within their families, but they and their teachers are grabbing for it anyway, in the most impressive and inspiring way.

“Your Life is in Your Hands” is one of many slogans a Kakhetian school used in its civics project to promote road safety in its village. But the message is far broader-reaching for the young people in schools countrywide being trained and funded by the USAID, PH International and MCK program “Civic Education,” now in its third round and supporting 650 schools. The program aims to help Georgia’s youth become more proficient in democratic principles, to develop student-led civics programs, and to provide technological resources to get students engaged in public democratic governance and social discourse.

Through the program, USAID and PH International partner with the Ministry of Education, Science, Culture and Sport of Georgia (MoES), local schools, and civil society organizations to institutionalize civics education as a key component of Georgia’s public-school curriculum. Key activities include enhanced teacher training and civic curricula, practical civic education projects, and support for student-led civics clubs.

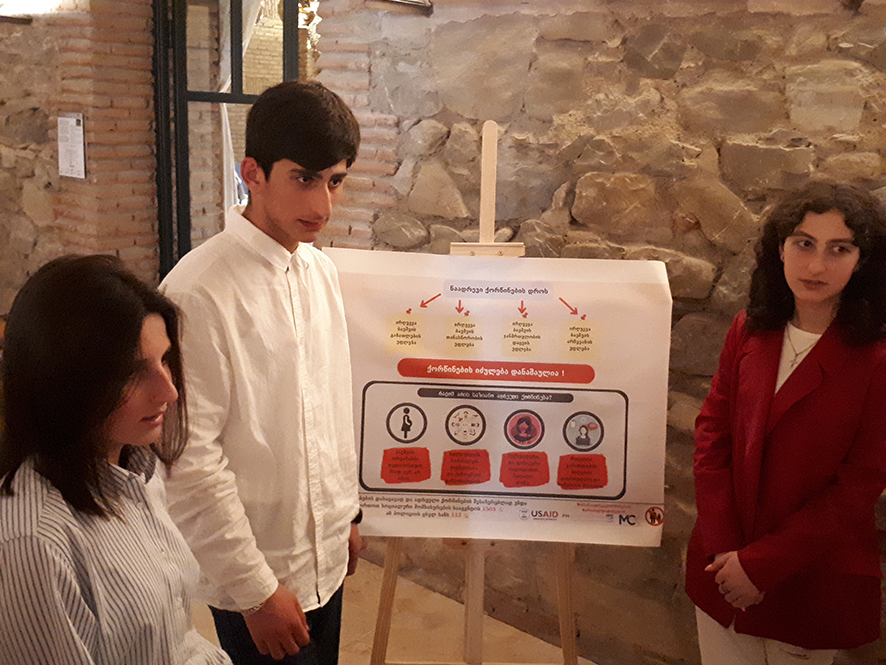

For some of the participating school pupils, the abovementioned slogan is painfully real – such as in Sighnaghi, one of whose schools is campaigning against underage marriage, a fact still seen in some villages in this region. Laws are in effect, but these often conflict with religious beliefs or community tradition. The children of the Sighnaghi school I met are hell-bent on raising awareness of the potential damage such practices can cause.

“We want to show young girls an alternative path to early marriage: the path to a good career. It’s not about having a diploma in your pocket, but about finding something you love and value to give back to society,” one student told us. She goes on to mention the guests they have so far invited to give career talks in school, and the excursions they have made to various local workplaces- a police station, a dentist’s, all with the aim of inspiring young girls to seek more out of life than marriage and child-rearing.

For others, “Your Life is in Your Hands” speaks of different kinds of opportunity, such as in the Lagodekhi school whose students speak Azerbaijani at home and learn Georgian as a second language at school – where, this year, they were united in a theater project that helped perfect their vocabulary and pronunciation in Georgian. Their teacher notes they are now waiting for an answer on a funding request to have a Tbilisi actor come and train the children via a six-month course. Such courses naturally go beyond mere “fun,” as the Azerbaijani children, with better Georgian, will be able to advocate for their rights within the country they call home, participate in political and social processes, and contribute to Georgia’s development.

Other awareness-raising efforts made by the various school students I met in Kakheti include promoting recycling, protecting local flora, providing career advice, and understanding democracy and why we need it.

In another Lagodekhi school, they came up with a map and app that provides information on the unique and interesting trees that grow in the town, and the need to protect them.

In Afeni’s school, the civics club students chose to highlight road safety, as the road in front of the school was commonly used as a drifting zone. They reached out to local authorities and companies for sponsorship to paint a zebra crossing and provide road signs. Until it is officially implemented, the children painted their own zebra crossing and filled each white stripe with slogans on safety, in this way reaching out to and involving their schoolmates and the local community, as well as (we hope) the irresponsible drivers.

“It is important to be a citizen and have a say. We have a responsibility to be active citizens, to be forward thinking, to create projects for a better future,” a Telavi student noted.

Such abovementioned projects, run by various-aged students in the schools’ civics clubs, see the children trained how to advocate for solutions, how to analyze, measure results, and communicate. They are guided on how to engage with relevant authorities – be they local politicians, local police, or businesses from which they wish to seek funding – and how to spread the word creatively within their schools and communities, seeing posters being printed or hand-made, flyers handed out in door-to-door visits with neighbors, or community events being held to bring people together for discussions.

On civics as a curriculum subject

From 2010, after some six years’ development, the Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia (MoES) began the slow roll-out of civics as a separate subject in the school curriculum. Initially, this was only for 9th and 10th graders. Since then, the subject has been introduced across the board.

Mariam Chikobava, of the Department of Schools and General Educational Development at MoES, took us through how civics currently works as a school subject in Georgia’s 2000+ schools.

1st grade introduces general ideas of civics education, while 2nd to 4th grade develops the concept of “my family,” “my school,” and expands toward the social environment, media and information, and the country as a whole. Over time, the subject increases awareness of why institutes exist.

For the first four grades, as yet, teachers need no specific qualifications in teaching the subject, and even those teaching higher levels are learning on-the go, coming from a background of teaching math or history.

We ask Mariam if there is a disadvantage in having non-specifically qualified teachers teaching civics. “At this stage, we are setting the standards we eventually want schools to follow, and are dealing with the issues step-by-step as they come up,” she tells us. “It needs a generation to change and is slow process, but it is progress, and in reality, we can’t just wait for the new generation to come into teaching. In many cases, the children enjoy the topic so much, it draws the teachers in and inspires them to progress.”

In 5th and 6th grade, historical events, legends, ethnographic traditions, and geographical elements are brought in to develop what the children touched upon in the first grades of study. Students are encouraged to discuss human rights, stereotypes, tourism, Georgian culture, and to identify issues in the community, to understand the need for a multiplicity of professions, and to begin to understand the need to handle their finances by saving their pocket money, for example.

From 7th to 9th grade, students are on to healthy living, caring for the environment, and they delve deeper into economic issues. At this stage, they expand beyond their own country, analyzing what it means to be a global citizen, as well as revisiting and developing upon human rights, and learning about governance, peace and conflict, bullying, cyber bullying, and how to advocate for themselves.

By 11th grade, and going into their last year of schooling, civics students look at business elements, risk analysis, political ideals, regimes, effects of globalization, global economy, crises, and more.

In the 2022-2023 academic year, older students are being obliged to create projects on a related civics theme of their choice. This means independent working in groups, as individuals, or as a class – with the teacher in a consulting role.

“This is a trial year,” Mariam notes. “There’ll be no grading of these projects – it gives both the teachers and students a chance to find their feet with the concept.”

The challenge continues, with the Ministry trying to give teachers freedom in what and how they teach, and battling the fear many “old school” teachers have of making mistakes, a fact which leads to their tendency to follow the books word for word, not leaving time for discussions, debate or creativity in the classroom.

A brilliant example of the shedding of “old school” teaching can be found in Telavi School No5’s civics club, run by the boundlessly energetic Zeinab Kakalashvili, who has a plethora of projects to show off – both of the current cohort of students and from past alumni who are now studying in universities abroad, with the lessons they learned being put eagerly into practice. Traffic safety, placement of a community bus stop, the fight for gender equality, the fight against domestic violence, awareness of the need for democracy and a fair vote when electing class representatives – these are just some of the topics the children have chosen to focus on and raise awareness about. And that awareness-raising comes in numerous inspiring forms- from printed or hand-drawn leaflets or posters, presentations to schoolmates and members of the community, to meetings with local municipality representatives, and also with businesses, with the goal of seeking funding for materials, technology or training.

Changing values, changing outlooks

GEORGIA TODAY sat down with Marina Ushveridze of PH International to discuss the progress so far, and the program looking ahead.

“This is the third 5-year project USAID has funded to support school-based civics education,” she tells us. “It kicked off a year ago and is supported by the Ministry of Education and Science of Georgia. We’ve added a new component to it, which is private sector involvement and the use of technologies in civics education. Where it started out focused on increasing the quality of civics teaching at schools and the practical activities of students (applied learning) in civics, now we’re working on a more supportive eco-system. School is a model of a mini state for kids. Whatever they learn in school, they practice later in life. That’s why school democracy is very important, not only to practice during civics class or in their civics clubs or student governments, but across all subject disciplines, so as to have a platform of shared values.

“We’ve seen a lot of progress in school-based civics education,” Marina notes. “Civics teaching has been introduced at all levels of schooling- primary school, middle school and high school, while, 10 years ago, it only appeared in grades 9 and 10, and only as a taught class- no projects or activities. This is big progress. The challenge yet to overcome is that a culture of civics and democracy does not yet prevail in schools. This is what we’re working on now. Our next goal is to help establish a democratic culture in schools, the concept of shared leadership, and the greater involvement of school administrations in supporting student governments. At this stage, student governments are still very much on paper, and are not so active. We want to make student governments stronger, as an important component of school democracy, together with their teachers, parents and school administration.

“We plan to work with MoES to create online civics courses, so it doesn’t matter where you are- you can participate in civics classes, meet teachers, and share and learn from each other. This will ultimately increase access to civics education. We will work with coaches who support the development of civics, and school leadership at the regional resource centers level, and we’ll bring in some international expertise to get us there.”

We next asked Marina about the USAID – PH International program’s latest innovation: The School Business Forum. The basic concept is to give the students, having identified issues in their schools or communities which need “fixing,” a chance to get funding for their proposed civics projects from local businesses. At the forums, which are held once per year in each region of Georgia, the students have to “sell” their projects to business representatives for financing. Before that, they get online training on writing and presenting, and the need to prolong their relationships with companies after financing.

“This is a totally new concept for them that needs to be taught,” Marina says. “We show them the need to engage their sponsors even after they receive funding, be it through the occasional phone call, email, or by offering an invitation to a relevant event. It shows appreciation and the fact they value the business’ contribution to what they are trying to achieve.”

And the concept seems to be working. There is growing interest from the private sector in supporting education. Top examples include Heidelberg Cement, TBC Bank, Biblus, Barambo and Bank of Georgia. In reality, education is the easiest thing to support- no-one can be against it, there’s no politics involved, and it’s positive for the company’s image.

“The Business Forum is an innovation which has been successful so far. It kicked off in October 2022. We’ve done nine so far and they went well,” Marina tells us. “Over 20 projects have been funded by different companies. Very often, local companies in those regions support students’ projects. We identify and make a list of businesses who operate locally, and we introduce the School Business Forum concept to them. We invite them as speakers to the schools, giving them a chance to speak about their corporate social responsibility strategies to an audience made up of students, teachers, school administration officials, and community members.

“Student preparation starts 3-4 months before the forum, and we help them shape their projects in a short and concise way so that they are clear and easy to explain to the business representatives they’ll meet. We help students develop their presentation skills, their ability to argue their views, to prove that what they are asking for is highly needed for the school, for young people.

“Businesses have been very engaged, asking a lot of questions, and sometimes they themselves work with the schools to adjust the project and align them more with their business interests. This is when kids learn how to negotiate. We also teach the kids not to get frustrated when their projects are not funded; to keep trying.”

We ask Marina about the sustainability of the USAID-PH International civics education project.

“Until Georgia’s democracy is fully developed, we will continue to need external support,” she tells us. “It was a very good decision to, with this third stage, create an ecosystem to support civics education in schools so that it is no longer dependent solely on USAID funding; so that the schools can continue to get support from the private sector even after this project ends.”

By Katie Ruth Davies