The number of hydropower plants being built in Georgia has slowed to a trickle in recent years. Shovel-ready projects have found it hard to move forward. The latest example is the $800 million Namakhvani HPP project, canceled after Turkish industrial conglomerate Enka terminated its contract with the Georgian government in late September following months of conflict and obstacles in moving forward.

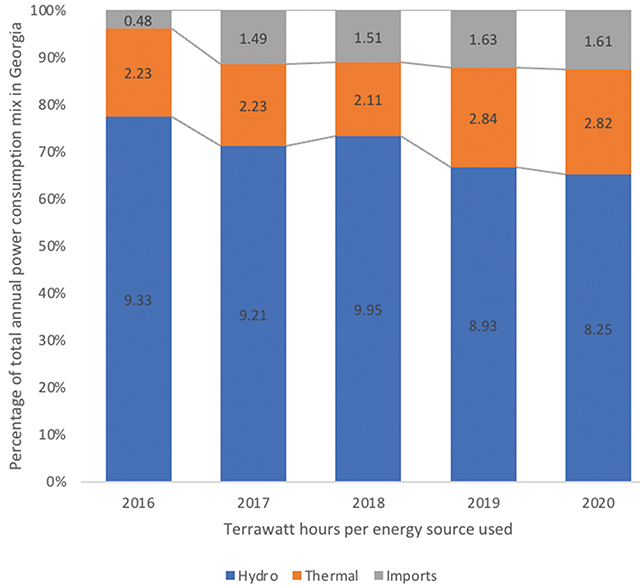

Renewable energy sources have even lost ground in the total share of Georgia’s total power consumption. Data from the Georgian electricity market operator ESCO show that in 2016, thermal power plants and imports accounted for just 22.9% of all electricity consumed in Georgia, while by 2020, the share of non-renewables and imports had increased to 34%, with the share of hydro sinking from 81% to 65% over the span of 2016-2020.

The hydropower slowdown is a problem not only because of the country’s obligations to the EU to move in step with the bloc’s plans to reach a net-zero carbon economy by 2050. 5% average annual growth in domestic energy consumption and the blossoming of a crypto-banana republic in Russian-occupied, breakaway Abkhazia have made Georgia a net energy importer since 2017, obliging the country to purchase between 11-13% of its annual electricity volume. Considerable dependence on natural gas imports from Azerbaijan and Russia to run the country’s thermal power plants further exacerbates the looming energy security problem.

A power purchasing agreement is a long-term electricity supply agreement between two parties – a power producer and a customer, often the state. The agreement obliges the customer to purchase a certain volume of electricity at a defined price over a set period of time. The agreement also stipulates when commercial operation is supposed to begin, and covers termination and other contractual issues.

Put entirely to use, Georgia’s annual hydropower generation potential is between 30-56 TWh per year, Norwegian Water Resources estimates in a recent report. At the high end, this is more than four times the volume of electricity the country currently consumes. Yet just a fraction of these resources are being used. Why?

Power purchasing agreements for all

Georgia was brimming with opportunities in hydropower in 2008 when the state launched a support program to promote investment in renewable energy projects, the main offering of which was power purchasing agreements (PPAs) on attractive terms.

Activity in Georgian hydro picked up around 2012, when the sector began attracting what some industry experts say was the wrong kind of interest: speculators looking to secure, sit on and pawn off PPAs when market prices would rise. Speculation itself isn’t always a problem, and can foster competitive market growth. But as of January 2020, the Ministry of Economy had a portfolio of outstanding agreements with approximately 60 HPP projects (currently at various stages of development) which had been awarded PPAs and which are now the focal point of a discussion about how – and whether – to push the country’s green energy agenda forward.

Can’t live with ’em

The IMF penned a letter to the Georgian government in 2017 advising the latter to determine whether it could weather the storm of financial vulnerability to which it would be exposed during a period of cyclical economic downturn due to its obligations taken on under the dozens of PPAs signed since 2008.

The Georgian Ministry of Finance calculated that the risk was indeed too high, and placed a moratorium on new PPAs that same year, claiming the state could face nearly 1 billion GEL (approx. $320 million) in exposure during the downturn of an 8-10-year economic boom-bust cycle, when it would have to purchase excess energy uncleared by the market due to the downturn in economic activity.

The calculation’s methodology assumes the construction and exploitation of all of the country’s outstanding hydropower projects that have been awarded PPAs (including the now-cancelled Namakhvani project, which alone would have accounted for a hefty percentage of the figure cited above), and a future market price of 6 cents per KWh, extrapolated from current import prices.

The ministry has since been nearly unwavering in its decision to put a pause on PPAs, and doubled down on its stance when Covid-19 sent the Georgian economy plummeting, which was “[a moment that] highlighted the importance of mitigating such contingent liabilities … and we used this opportunity to announce a more complete moratorium on PPAs”, the ministry’s Head of Fiscal Responsibility Department, Shota Gunia, told Investor.ge.

The ministry’s goal is not to interrupt investments, Gunia stresses. “The MoF is responsible for ensuring sustainability. Our interest here is not in the quantity of investments, a phenomenon we have seen in the past, but in their quality. We see PPAs as a serious contingent liability, and we believe there are alternatives that will be acceptable to both the state and the private sector.”

The Ministry of Finance concedes that the calculation methodology could be construed as contentious, but notes that the important takeaway is that the exposure is ‘very large’ and that both the IMF and the World Bank allegedly share the MoF’s “opinion and feeling of alarm about the situation.”

Other reasons the MoF remains skeptical of PPAs pertain to budgetary concerns: “When you disclose information in the state budget, the parliament doesn’t know that this [PPA] liability exists because it’s contingent, which doesn’t exactly go into the balance sheet. It’s in the annex. So it is a kind of tool, a conduit, that can be used for financial misconduct. We want to ensure this doesn’t happen.”

In place of PPAs, the Ministry of Finance has offered developers the incentive of feed-in premiums (FIPs) – a guarantee of up to an additional 1.5 cents on the kWh, with the final price not exceeding 5.5 cents.

The offer has not gone entirely shunned. The ministry claims more than 25 projects with a potential total installed capacity of 525 MW, that’s about one-ninth of Georgia’s current generation capacity, have either agreed to sign up for FIP agreements or transitioned from PPAs to FIPs since the introduction of the mechanism in July 2020. However, many of these projects already had expiring PPA agreements, and decided to proceed with FIP agreements to avoid walking away entirely empty handed. Whether these long-standing projects will continue on into development is another question.

FIPs address the MoF’s budgetary concerns, says Gunia: “The FIP system reduces liabilities enormously. And here, they’re not really contingent liabilities: we can budget for this. It becomes a line item approved by Parliament. This solves the transparency issue for us.”

Can’t live without ’em

But FIPs don’t address the concerns of the private sector, which remains largely unconvinced.

Georgian Renewable Energy Development Association (GREDA) CEO Giorgi Abramishvili says that the Georgian market is too small and the future price of electricity on the upcoming competitive energy market, due to launch in March 2022, too unpredictable to justify investing in new projects at this time without the provision of incentives more substantial than feed-in premiums.

“PPAs can cover the financial risks of operating on a market with as many unknowns as Georgia, at least for a time until the competitive power markets are operational. It is unimaginable that investors will come without the restoration of PPAs,” Abramishvili says.

FIPs do not appear attractive to either investors or financial institutions, the GREDA chair notes, and may even pose two serious risks to project profitability in the face of the new market: “State-owned HPPs such as the Enguri HPP [ed. which accounts for more than 35% of energy consumed on Tbilisi-controlled territory] have too much clout in setting the market rate because of their large production volume and low tariffs. Power plants that come online with FIPs too early could end up exposed to the downward price pressure. What investor wants to take on that risk?”

Similar potential pressure lurks outside Georgia’s borders as well: aggressively predisposed neighbors could strike a serious blow against Georgia’s energy sector by taking advantage of the country’s liquid-market-to-be through dumping, rendering FIPs unsustainable.

Therefore, Abramishvili argues, PPAs must be retained, if only for their value as price floors, and provide security for banks, investors and the grid as a whole.

Many in the private sector say feed-in premiums may be a great target for the future, several years after the power sector has settled following competitive market reforms. This will allow for the generation of real market prices, and only then will the offerings of an FIP system be worth assessing.

But Georgia doesn’t have the luxury of being able to wait years before continuing the pursuit of a green future. Focusing exclusively on current power needs means the country could end up more dependent on dirty power: fossil fuels and gas-fired thermal generation from its neighbors.

It is already clear that this is what is happening on the market in the absence of state support for clean energy. The Georgian National Energy and Water Supply Regulatory Commission’s (GNERC) annual report shows that generation capacity grew 5.6% (253 MW) in 2020, of which 230 MW (91%) was accounted for by the installation of a thermal power station in Gardabani (read – gas from Azerbaijan). The six remaining HPPs added just .5% generation capacity in 2020.

Private sector investors have objected to the position taken by the Ministry of Finance on other grounds as well, one of the first and foremost being that some level of risk is unavoidable when building an energy portfolio for the future, if only because of the rate at which power plants’ operability declines (approximately 5% yearly over the long term).

The nearly 1 billion GEL ($320 million) exposure has to be further measured against the fact that the country’s consumers are already spending $50 million a year on imports to cover shortfalls in domestic energy production, which would outweigh the expected shock of an 8-10-year economic cycle downturn. Moreover, there is an argument to be made that the potential loss of 1 billion GEL spread out over nearly a decade in an economy with a gross annual GDP of nearly $16 billion is stomachable to keep the lights on and ensure energy security.

To boot, the billions of dollars in investments (the Namakhvani HPP alone had a projected investment size of $800 million) behind hydropower plant projects offer substantial tax revenue streams, both at the initial construction stage and once in operation. Furthermore: one kilowatt hour produced in Georgia has a different economic value than one KWh that has been imported. Energy produced in Georgia means jobs and taxes, in addition to improved energy security, all of which would have to be weighed against the risk of facing a large theoretical payout in the future.

A final point: mechanisms are in place on both the current and coming markets to prevent arbitrary energy production and subsequent unjustified claims to payment from state coffers. Grid operator GSE currently has a dispatch license and can control production levels; power plants are unable to generate power in situations where it is not needed. On the coming markets, however, power plants will have more freedom to schedule production, and will be rewarded for correctly forecasting additional needed resources, but will also be penalized for oversaturating.

Hope for compromise?

Whether or not PPAs present serious fiscal risks to the state budget is debatable, and there are a number of other issues facing the sector.

A spokesperson for the 5-year USAID Securing Georgia’s Energy Future program told Investor.ge that the implementation of the competitive energy market mentioned earlier is absolutely critical, as it will provide potential investors with access to real data about local market conditions and prices.

Energy pundits in the country often say that political resolve to push the country’s energy sector forward also seems lacking, particularly in light of Enka’s recent decision to terminate its contract with the state, which may have repercussions for the energy field for years to come.

“Regardless of the myriad of issues, taking a long-term approach is necessary to ensure stable growth in Georgia’s energy sector,” says the USAID Securing Georgia’s Energy Future program spokesperson. “Demand has grown steadily in the past decade, faster than generation has been able to keep pace with, even with the addition of gas-fired power plants. PPAs may have their associated issues, but they are critical for the bankability of projects that the country so very needs.”

But there’s a caveat here: PPAs only have to remain a part of the local investment ecosystem for a limited period of time. Indeed, Georgia’s power market is scheduled to ‘go liquid’ in 2022, and long-term PPAs could distort market prices:

“So, what we really need is a ‘transition solution’”, the spokesperson notes. “One of the potential compromises we’ll be promoting will-be agreements based on five years of a PPA, and an additional five years of an FIP, to ease in new plants.”

There are yet other compromises the program says warrant discussion. Stalled HPP projects with PPAs could be reworked, or their license rescinded to make room for other potential plants which have a chance of meeting with less public resistance and running up against less red tape and technical barriers. Yet another interesting proposal: a mechanism that would adjust PPA payments against project IRRs, addressing concerns that PPAs could pose large fiscal risks to the budget, while assuring investors that returns would be guaranteed to a certain extent.

In response to the issues mentioned above, the Ministry of Finance notes that its “existing PPA portfolio highlights that [it] has an appetite for risk,” but how that will manifest in a more secure and eco-friendly future for the country’s power sector remains to be seen.

Published with permission of Investor.ge.

By Josef Gaßmann for Investor.ge