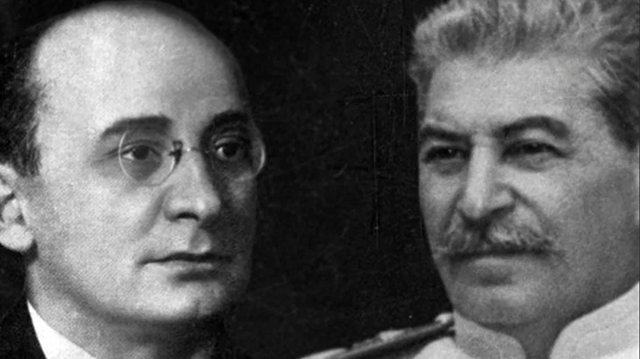

We know many things about Lavrenty Beria, the Community Party’s secretary in Georgia from 1931-1938. While his mark on Tbilisi’s skyline is well known, Beria’s legacy also includes a less well known system of tunnels under the city streets. Very little is known about the tunnels. Today, there are more legends and crumbling walls than documented facts for historians to study. Beria is well known for his role in the atrocities perpetrated on Stalin’s orders – as well as his heavy hand in city planning for Tbilisi. Under his watch, the city circus and post office were built, as well as the parliament building on Rustaveli Avenue.

He is also credited with overseeing major infrastructure projects like the construction of the Right and Left banks along the Mtkvari river, cultivating a veritable forest from Tskneti to Mtatsminda Park, and creating the city’s sewage system.

It is in the sewage system that faint traces of his lesser known project can still be seen: a system of tunnels that traversed the city underground. There is virtually no information about Beria’s underground projects in the state archives, and no indication of them on large-scale Soviet-era maps of Tbilisi. The evidence of the tunnels that does exist, however, mirrors some of Beria’s pet building sites.

For example, under the former Institute of Marxist-Leninism (now being rebuilt as a hotel), there are remnants of what appears to be a tunnel leading from a prison under the building to the River Mtkvari. A tunnel is also rumored to exist under the parliament building (which once served as the Communist Party’s headquarters) – legend has it that even former Georgian President Zviad Gamsakhurdia made use of it during the last pitched days leading to his overthrow – and what is believed to be the collapsed remains of a tunnel, which was locked closed, in the courtyard of Beria’s former house (now Georgia’s Olympic Committee).

A professional excavator, Roma Khatoevi (known among in the excavator’s society by the nickname Fabian), the founder of Tbilisi urban exploration website Fabi.ge, has extensively researched various tunnels built under Beria’s rule.

On his site, Khatoevi maps out a tunnel stretching from the Circus building on Heroes’ Square in Saburtalo to the left embankment of the Mtkvari river, somewhere in the neighborhood of Aghmashenebeli Avenue.

Another tunnel, in the Tbilisi Botanical Garden, indicates Beria was well acquainted with the city’s underground architecture and built onto existing tunnels as needed. The tunnel in the garden was first built during Nicholas II’s reign and later enlarged. There has been speculation that it once connected to tunnels in the center of the city. Since Beria’s time, it has been used alternately as a secret laboratory under the Soviets as well as a short-lived nightclub. It is now closed.

One of the longest tunnels Khatoevi has documented on his site reportedly wraps around behind the Rustaveli underground station for an estimated 2,500-3000 meters. Another tunnel winds under the city for nearly a kilometer and links the former NKVD office on Constitution Street to the Tbilisi Central Railway Station.

With no mention of the tunnels in the archives, historians and scholars can only speculate about why Beria and his comrades built the tunnels and what purpose they served. For instance, it is believed that the tunnel leading to the train station could have been used to secretly transport prisoners out of the city.

Beria’s own reputation as the ruthless head of the purges in the South Caucasus adds credence to that theory: there was not enough room in the prisons in Tbilisi to house the hundreds of people jailed, tortured, and killed in the years spanning the cycles of repression in the 1930s. So it is natural, reasoning goes, that the government needed a way to quietly move prisoners and corpses.

Another theory, however, is that the tunnels were part of a safety/contingency plan Beria created in case he needed to escape from the city. For instance, Tbilisi’s metro system was conceived as part of a wider strategy to shelter people from the NATO attack Moscow feared would take place once Turkey joined the military alliance in 1952. But the tunnels that have been discovered so far are believed to date back to the 1930s, making them too early to be part of the Soviet government’s Cold War strategy.

Regardless of why the tunnels were built or what purpose they served for the Communist elite and the state’s secret police, Beria apparently took the experience to heart: in the darkest days of World War II for the Soviet Union, when Stalin feared the government might fall to Hitler’s army, he commissioned Beria to build vast bunkers in cities around Russia.

Few still exist. However, in Saratov, one of Beria’s tunnels remains intact. The underground bunker Beria built is believed to be able to withstand a two-ton bomb and uses systems similar to those on submarines to provide electricity and air conditioning.

The Tbilisi tunnels do not appear to be as well fortified. But as long as construction continues to uncover more pieces of the city’s past, the chance that someday Tbilisi will resolve the legacy of Beria’s tunnels still exists.

BY EMIL AVDALIANI