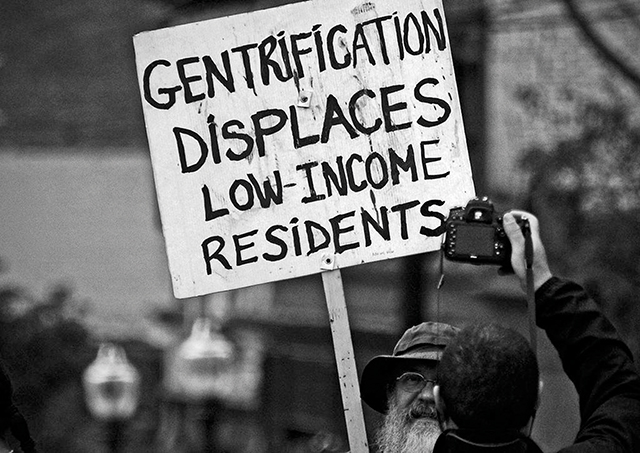

Changes in social, economic, and political processes are accompanied by the emergence of new terms, one of which is “gentrification.” This term is quite new for Georgian society.

The term gentrification originated in England in the 1960s and was used to describe current events. The classical gentrification process described such real estate conditions where the rental market was dominant over the owning of property. This aspect has great importance in understanding the phenomenon of gentrification, both in England and in Central Europe, where a huge part of the population lives mainly on rent and does not own property.

Gentrification implies a process when in the city center or near the center, historic neighborhoods are undergoing renovation, where such places are otherwise uninhabited and less attractive for living in. In Tbilisi, the first renovation started in the 1970s, but it was a very slight process; in the Soviet Union, the focus was on building new residential areas rather than renovating the old historic city, and the only renovation done at the time was on balconies built out on buildings in the old Kala district. The classical renovation of the city in Tbilisi began only in the mid-2000s.

In order to better analyze the gentrification processes, GEORGIA TODAY sat down with architect Luka Bakradze.

“Gentrification processes in Europe began in the following way: in districts that were not renewed and were in a complex condition, the rental price of an apartment was low; however, these districts had two attractive components, one – a low rental price, and two – a downtown location,” Bakradze tells us.

“Because of these two components, these neighborhoods were taken up by the low-income creative class: students and artists. In urban sociology, they are called pioneers; finding such neighborhoods and moving in, which itself leads to the revitalization of these neighborhoods. As students and creative people move there, social contacts take place, attractive activities emerge, cheap cafes open, public life comes to flourish. This process is usually followed by the first steps of development: cultural destinations, galleries are opened. Public life is revived there and development bring changes to the community, hence the attractiveness of these neighborhoods increases. As a result, those places become subject of interest for other social classes, and the financially strong part of the population begins to become interested in such neighborhoods itself,” he says.

“With the increase in demand, apartment rent increases, and the financially lower class, the creative class, can no longer afford to stay in this area, and the financially strong class takes over the neighborhood. Moreover, landlords seek to oust old tenants in favor of those with better finances. This process is more difficult in Europe than in Georgia, but there is still a lot of leverage to force them to leave these places.”

In Georgia, the situation is a bit different, right? Those who are evicted, in most cases, are the owners of these houses.

“Yes. Classic gentrification is precisely a rent-based phenomenon. In the case of private property, slightly different processes take place. Consequently, we cannot classically call the ongoing processes in Tbilisi ‘gentrification,’ because there are private apartment owners in Tbilisi. It is their decision whether to leave this apartment or not; therefore, the classic European gentrification in sociological terms cannot be applied to the inhabitants of Tbilisi,” Bakradze says.

He highlights that European urban renewal implies the renovation of public infrastructure and not the renovation of houses and flats. The process of urban renewal makes these neighborhoods even more attractive to the financially affluent. First, the creative class makes these neighborhoods interesting, and on top of that, the renewal of infrastructure makes those places more attractive.

“For example, where I live in Berlin, in Prenzlauer Berg, first, when I got here, in the early 2000s, the neighborhood was in a very poor condition and financially low, but the creative community found this place and it became a very attractive destination. There was always something going on, nightlife was very active, there were cafes, clubs, and in the late 1990s and early 2000s, the city even carried out renovation activities there and the public infrastructure was significantly upgraded and improved. As a result, Prenzlauer Berg has become the most expensive district in Berlin, and today the population here has completely changed and only the wealthiest people live here. It can be said that the change of population has had repercussions in public life, as nowadays the place is a dead district. At 8 o’clock, it is hard to find people on the street because there live wealthy people who work during the day and have to go to bed early in the evening,” Bakradze notes.

“It was a very clear example following the intervention of the state, and this is one of the first urban renewals carried out in the early period where the state and city did not think about what the process of urban renewal might lead to.

“This case turned out to be a great lesson; the government added a lot of leverage to limit and hinder the gentrification wave, to keep the local population from flowing out of such neighborhoods.”

Back to Georgia- how are the renewal processes going?

Consider, for example, Gudiashvili Square. The rehabilitation began with the evacuation of the population. Renovation of the city cannot be started by pulling the population out. As result, those buildings have been empty for years and still are empty to this day. When these processes started, I asked the governor a question that we can ask now too: Why is the city being renovated and for whom are we renovating the city? What do we want to achieve? You want to have a beautiful building, but who is it for? What do the city and the community gain from one beautiful building? Classically, the understanding of European city renewal lies in improving the living conditions of the people living in the area. The living environment should improve so people feel better and become more productive and so on.

Returning to the Gudiashvili example, we can say that we got an ugly, inverted situation: They did not do the renovation for the people of the city, but on the contrary, they got rid of them altogether.

So these places are being renovated for tourists?

Maybe, but why do we do it for tourists? How does it benefit me, as a resident of Tbilisi, if a tourist likes a house? I should gain something, right? Since the government is doing the renovation, that means I’m paying my taxes so that house looks beautiful for tourists? All this leads to the fact that I am renovating the house so that the source of income is tourism. Let’s follow this logic. If we follow this to the end, we may want tourists to like it all, to come and eventually go to the point where we want to earn more revenue from tourism. But then what are we saying? That our stated policy is to make Tbilisi attractive for tourism and people should gain income from tourism? The economic direction of the city should focus on tourism? In other words, we must come to the conclusion that Tbilisi is a city that lives on tourism.

We also know from the European example that tourism harms cities far more than it benefits them. For example, when I arrived in Berlin, it was a very attractive place because it was not yet damaged by tourism.

“Due to tourism, many Berliners, and me too, avoid going out. That part of the city is ruined by tourism. Take the example of Amsterdam, a famous tourist destination which any Dutchman will tell you is not a place worth living in anymore. Tourism is ruining cities, and European society has realized that. There are many more negative than positive developments in tourism. Therefore, it is wrong from the beginning that we should renovate Gudiashvili Square for tourists. It is wrong to renew Tbilisi for tourists.”

Bakradze suggests that instead, Tbilisi should be renewed for the residents of Tbilisi, for local society, so that people can live in dignified conditions. To live, work, rest, raise children in a proper environment. This is the first goal of renovating the city and, consequently, the district, the building, will be good for tourists as well. The starting point should be that this district, city, or square is a healthy living environment for the population of Tbilisi.

“Consequently, to go back to the conversation on the emptying of the Gudiashvili population, this process was wrong from the very beginning,” Bakradze says.

Does the outflow of the population and entering only the financially strong part of society lead to the segregation of city residents?

The direct result of gentrification is precisely the segregation of the population. When an indigenous, low-income population is replaced by a financially strong population, on the one hand, only the financially strong population remains in the area, and this distressed population has to move somewhere, to an area where the real estate price is low. In the suburbs, therefore, is a classic example of how the city is segregated, where the rich live in one place and the poor in another. A socially divided city is an unequivocally negative phenomenon where ghettos form, often resulting in crime.

Tbilisi was and still is a rather mixed city compared to European cities. Segregation did not take place in Tbilisi during the 19th-20th centuries and it was a positive city in this respect. One way or another, it is still like that, but cases like Gudiashvili, supported by the government, will sooner or later see Tbilisi becoming like other European cities: a segregated place, and this will be a highly negative event. Every city government is trying and should try to avoid segregation and consequently the problems of gentrification, not only in those areas where it is carrying out urban renewal, but also in areas where the government does not participate, so that replacing the existing population with another part of society that is homogeneous, does not occur.

By Ketevan Skhirtladze