Tbilisi is a city irrevocably shaped by its rivers. Over a dozen rivers of significant size, as well as innumerable intermittent streams, join the main artery of the Mtkvari in the territory of the modern city. The deep channels, valleys, and canyons carved by these flows of water since time immemorial have granted Tbilisi its present form, and the story of the city’s development is inextricably tied to the challenges and opportunities given it by its waters.

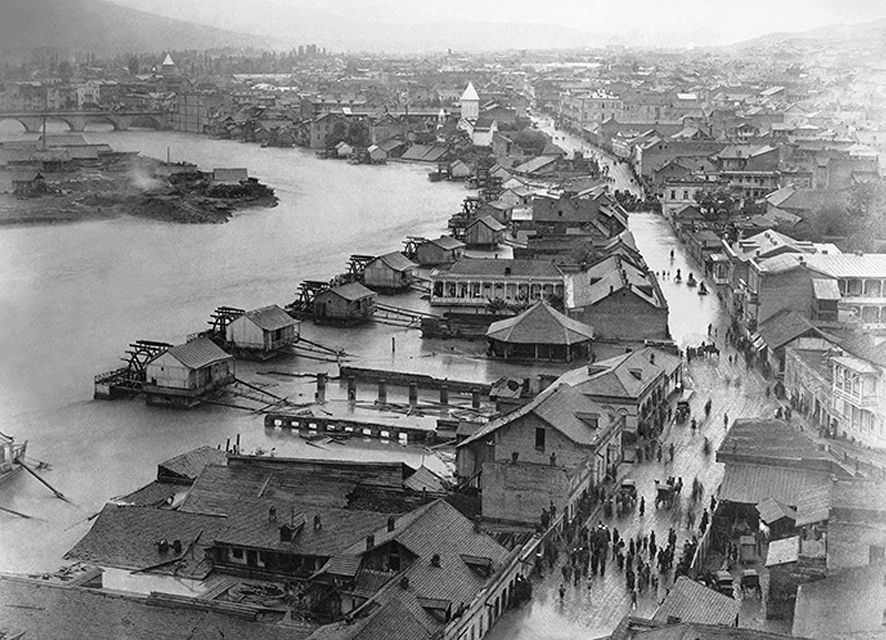

The oldest part of Tbilisi is located at precisely the narrowest point of the Mtkvari, where it cuts a channel between two rocky cliffs – Metekhi on one side and today’s Meidan on the other. Throughout most of Tbilisi’s history, its rivers and waters were a much more present element of the urban experience than they are today. Drinking water was well supplied from springs around the perimeter of Mtatsminda and Narikala – many of which still exist today, hidden in Asatiani street courtyards. The three historical rivers of Sololaki – Samarkhakhevi, Avanaantkhevi, and Tsavkisistskali – provided plenty of extra water for washing, and the Mtkvari itself gave its power for transport and industry.

Over time, the system of bridges we are familiar with today connected the two banks of the valley, but ferryboats and even log rafts remained important modes of moving about town into the 20th century. As Tbilisi industrialized, floating watermills extending into the Mtkvari provided power for many different kinds of workshops. Tbilisi’s rivers provided its citizens with entertainment as well – the Ortachala Gardens were a lush picnicking ground on a large island full of fruit trees and grapevines, where Tbilisians of all different classes met, mingled, and drank wine.

Taming Tbilisi’s Rivers

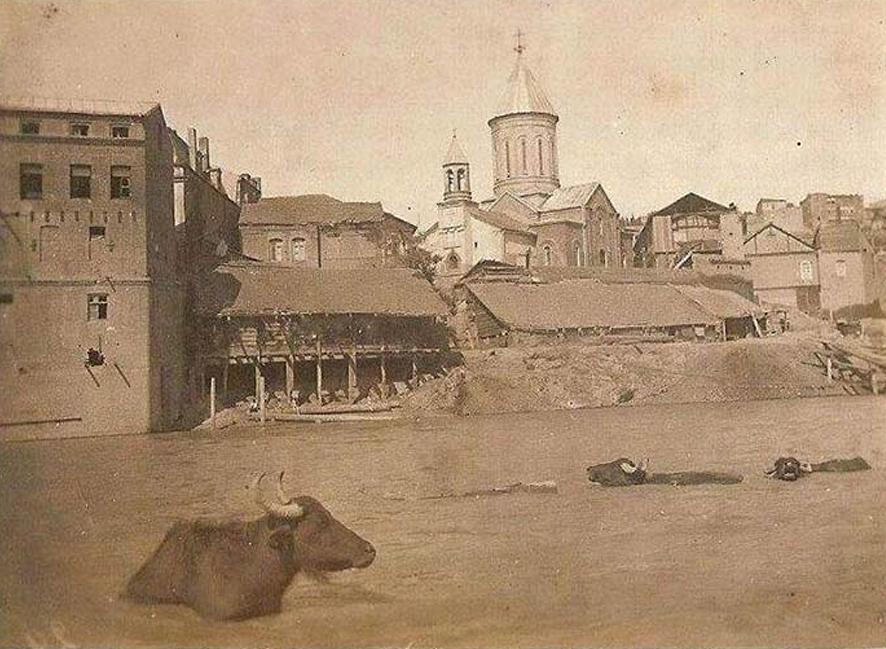

But untamed rivers also posed perils for the growing city. Spring rains would cause the Samarkhakhevi and Avanaantkhevi to burst their banks and carry mud and debris down the streets to today’s Liberty Square. As a result, they were the first of Tbilisi’s rivers to be abolished. Today, they flow in a large culvert underneath the Old Town, escaping the awareness of nearly everyone who walks above. The expanding city also faced a major obstacle in the steep, overgrown Varaziskhevi, which can be translated as “Boar’s Ravine,” until a toll bridge was constructed allowing easy access to the then pasturelands of Vake. Worst of all, the Mtkvari itself would flood catastrophically from time to time, bringing death and destruction, and sending residents of the Rike neighborhood out of their houses in rowboats.

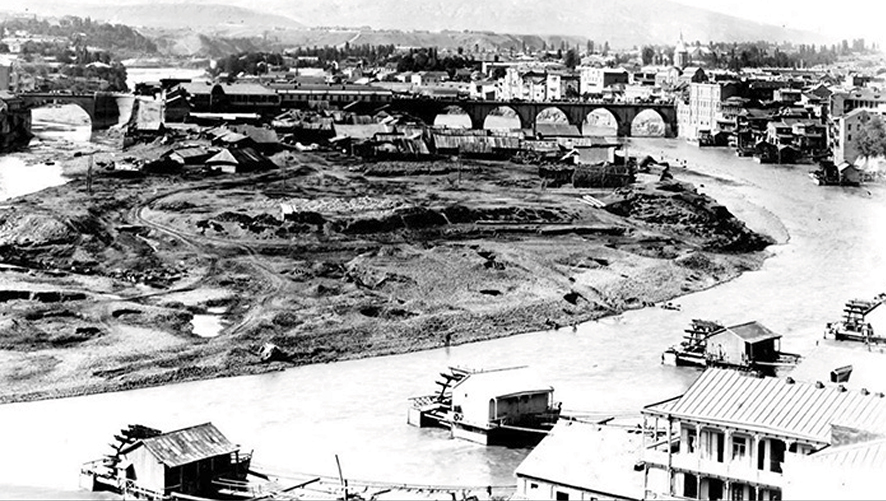

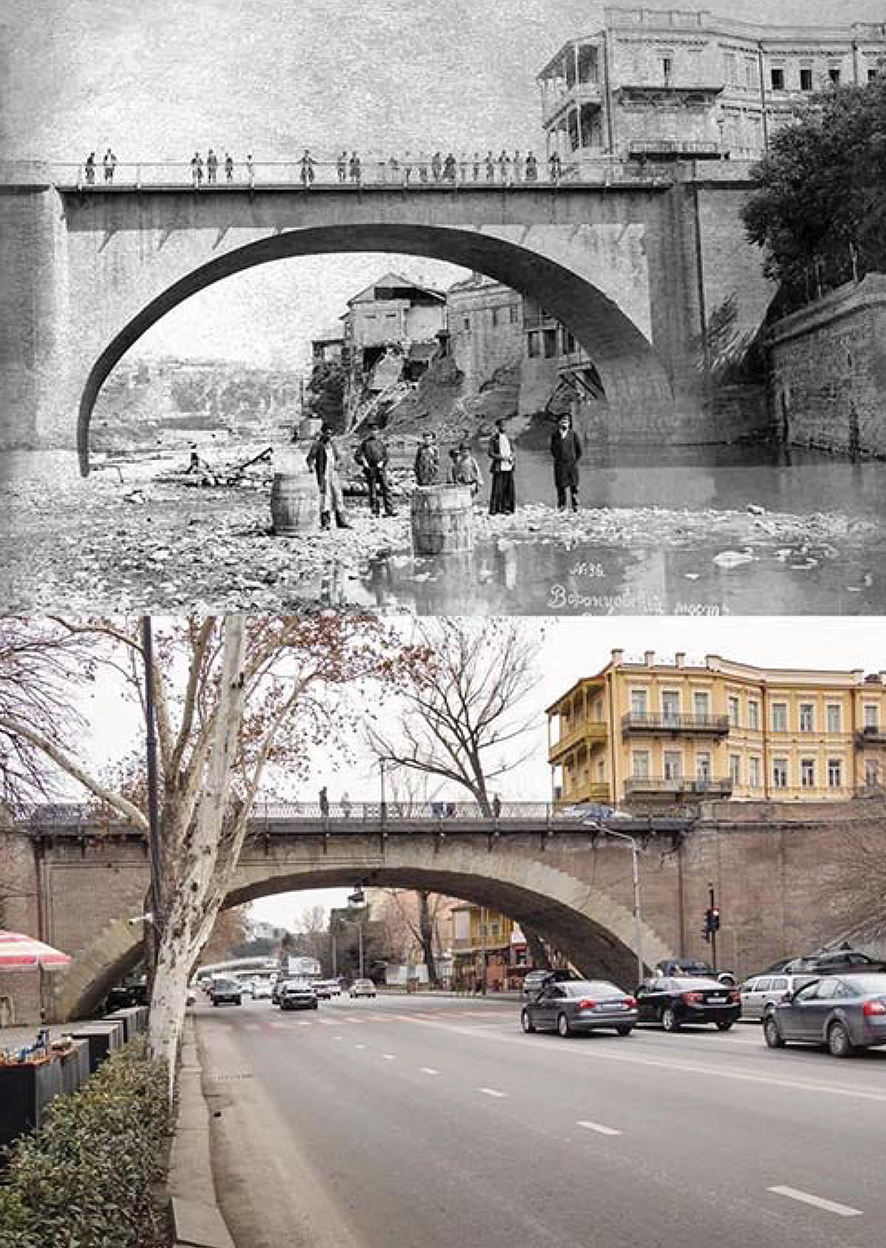

It was under Soviet rule that Tbilisi’s relationship with its rivers began to change drastically, from the conditions that had essentially been in place since the beginning of its history to that which we are more familiar with today. Perhaps the most thorough transformation began in the late 1930s, under Lavrentiy Beria’s brutal governance of the Georgian SSR – the construction of the Mtkvari embankments. Entire swathes of the historical city, which had until then crowded up to and towered over the river, were pitilessly bulldozed, including many ancient churches and the stunning 16th-century mosque which had stood in the Meidan.

This emptied space along the right bank was transformed into a flat, paved highway along which the new axis of transit would develop for Tbilisi. The old watermills, ferry boats, washerwoman’s shallows, and buffalo wallows vanished in pursuit of the cleanly lined plans of socialist modernism. The left bank’s embankment would follow in the 1950s, effectively cutting off Tbilisi’s access to its river. The shallows under the Dry Bridge were filled in, and the Madatov and Ortachala islands were attached to the mainland. Two dams at Zahesi and Ortachala brought the ebb of the river under human control, banishing the risk of flood forever.

Elsewhere, the Varaziskhevi was filled in and the modern highway, along with Kekelidze Street, were built in the newly dry ravine. Diversion canals from the Iori transformed the three natural lakes on the north side of the city into the Tbilisi Sea. As the 20th century progressed, Tbilisi rapidly expanded, with massive development projects incorporating previously rural areas like Gldani, Dighomi, and Krtsanisi to the city. The rivers of these districts were also dealt with in one way or another – some diverted to the drainage system, others reinforced with concrete channels, still others left in place as a kind of forgotten no-man’s-land.

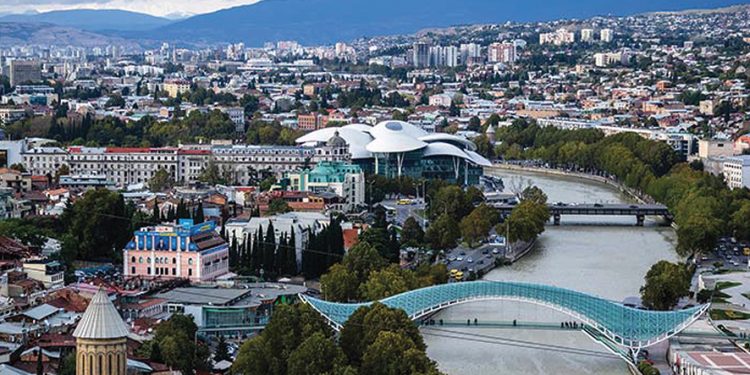

Today’s Tbilisi

Today, Tbilisi’s rivers occupy a somewhat nebulous and haphazard place in the experience of its citizens, as well as in the development plans of its administration. In contrast to the scenic riverside promenades of many European cities, the Mtkvari remains largely isolated from Tbilisians – it is experienced as a choke point and an obstacle to the free flow of transit, and only Dedaena Park in the center allows people a chance to come close to it. Its tributaries do not fare much better; if a water flow still exists above the ground in Tbilisi’s territory, it is most often inaccessible, overgrown, full of trash, and polluted by sewage discharge. Development planning, on both the public and private level, frequently does not take the health of river hydrology and ecology into account. Most notably, in recent years, calls for the transformation of the Vere River into a large green corridor between Vake and Saburtalo were rejected, and a new highway was built through the valley instead; unfortunately, design errors in this project led to the catastrophic exacerbation of the flash floods in 2015.

In spite of their neglected condition, however, Tbilisi’s rivers continue to flow. Those that have not been completely channelized and retain their natural banks provide unique natural habitats for all kinds of plants, birds, insects, and reptiles in the increasingly inorganic urban environment. A glance at satellite imagery reveals occasional streaks of green between the gray buildings, betraying the presence of a remarkable diversity of life.

Advancements in engineering have rendered the perils of urban rivers a thing of the past, while access to natural spaces is increasingly considered a necessity for urban residents. It is to be hoped that the continued development of Tbilisi will place a greater importance on the role of rivers in the planning of the urban landscape. Tbilisi is a city in desperate need of more parks and green spaces, and its rivers still naturally provide that. Following the example of many cities around the world that have successfully restored their urban rivers, Tbilisi could clean up, landscape, and create access trails through the many rivers of its various neighborhoods with minimal investment, reversing its Soviet heritage of isolation from natural spaces. This network of green corridors and recreational spaces would be sure to improve the quality of life of Tbilisi’s residents, as well as its urban ecosystem, and Tbilisi’s rivers would once again take their rightful place as a formative element in people’s experience of the city.

The Vere valley still hosts some of the largest green spaces in Tbilisi, but the riverbanks are neglected and overgrown, and direct discharge of sewage into the river gives it an unpleasant smell. A municipal project for the restoration of the Vere river’s ecosystem would provide great benefits for the residents of Saburtalo and Vake.

*Timothy Merkel is a musician, tour guide, and activist residing in Tbilisi. His project documenting the locations and conditions of Tbilisi’s hidden rivers can be followed on Instagram: @riversoftbilisi

By Timothy Merkel for Investor.ge