OP-ED by Rauf Mammadov

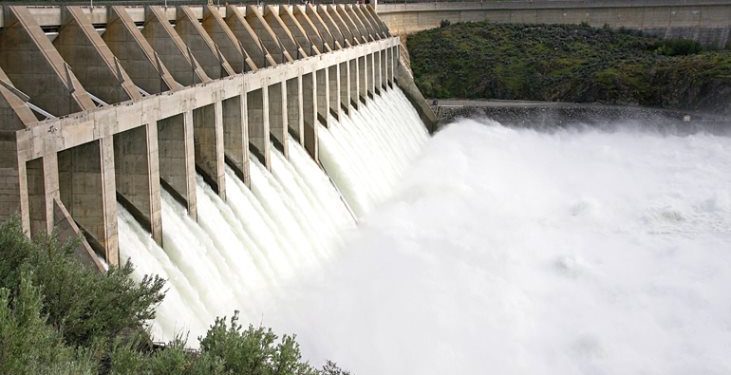

Social and environmental concerns over a hydroelectric power plant at Namakhvani in Georgia are valid, but there are wider economic and geopolitical considerations at play too.

In 2019, the government of Georgia signed a 15-year agreement with the ENKA Renewables Consortium to build and manage the Namakhvani hydropower plant in the west of the country.

- Montenegro starts offshore oil exploration, worrying environmentalists and anti-corruption activists

- The fate of Lake Balkhash is fueling anti-China sentiment in Kazakhstan

- Lithuania is well placed to lead on clean energy

Bringing in a direct foreign investment of 800 million US dollars, this 433 MW power plant is expected to revolutionise Georgia’s electricity system, reduce its energy dependence, and assist the country in meeting its commitments under the Paris Accord.

Electricity consumption in Georgia has followed an upward trajectory over the last decade and levels are forecast to reach 20 billion kWh by 2030, almost double the country’s current consumption.

Hydropower plays an indispensable role in Georgia’s electricity supply, accounting for 72 per cent of the country’s electricity. Bereft of fossil fuel resources and rich with mountains and rivers, hydropower plants have become a natural solution to meet the country’s electricity demand. There are more than 80 large and mini power plants across the country.

As with other hydropower plants built in Georgia, Namakhvani has caused some concern amongst local populations and environmental activists. While hydropower is considered a renewable energy source, hydropower plants can directly and indirectly impact local populations and aquatic and wildlife ecosystems.

Georgia’s local associates of the NGO Green Alternative has led protests against the project, arguing that proper environment and social impact assessments were not conducted prior to the government announcing the agreement.

Wider considerations

These social and environmental concerns are valid and should be addressed by the government of Georgia. But there are also wider economic and geopolitical considerations at play.

First, the majority of the country’s energy is produced at the Enguri hydroelectric station in Abkhazia – an internationally recognised region of Georgia but one which Tbilisi does not currently exercise sovereignty over. Tbilisi has reached an agreement with the Russian-supported breakaway region to receive 60 per cent of electricity produced by the plant but this situation has prevented Enguri from reaching its full potential.

Georgia is also affected by the seasonality of its hydropower plants. While 52 per cent of its electricity is produced by year-round plants, the country is reliant on seasonal power plants for the remaining 20 per cent. This dynamic has forced an unprecedented increase in electricity imports from abroad, predominantly Russia and Azerbaijan. In fact, Georgia’s electricity imports reached a four-year high in February-March 2021 – accounting for half of its total imports.

Those protesting the Namakhvani project have called on the government to revoke the permit granted to the ENKA Renewables Consortium on the grounds that legal processes have not been adequately followed. However, the government has insisted the bidding process was fair and transparent, with the consortium outbidding 25 other companies to win the rights to build, own, and operate the plant.

According to the International Energy Agency, Georgia has made solid progress in improving transparency in its electricity sector. Georgia became a contracting party of the Energy Community Treaty in 2017 and has since intensified its efforts in implementing legal and institutional reforms aimed at aligning its energy sector with EU regulation for electricity and gas markets.

A step towards energy independence

The Namakhvani project is a step toward energy security and independence for Georgia. With rising energy demands, exacerbated by the seasonality of hydropower plants, Georgia has been forced to increase its electricity imports from abroad, notably Russia. Namakhvani is expected to supply 12 per cent of domestic demand, going some way to reduce this dependance on Russia while generating new sources of economic revenue.

Namakhvani can also strengthen Georgia’s position as an energy exporter. Neighboring Armenia has long been a favoured energy corridor in the region but its conflict with Turkey and Azerbaijan has left the country hostage to Russia. Georgia has the potential to serve as an alternative energy transit country, connecting Caspian oil and gas resources to European markets.

In strengthening its domestic production capacity in the power sector, Georgia can also become an exporter to neighbouring countries, contributing to regional integration of energy markets.

Russia believes the countries of the region should remain in its sphere of influence and struggles to tolerate their economic and democratic development. Namakhvani is crucial to realigning some of this power imbalance while thwarting Russian ambitions for dominance, but social and environmental concerns around the project must be addressed first.

Unlike many news and information platforms, Emerging Europe is free to read, and always will be. There is no paywall here. We are independent, not affiliated with nor representing any political party or business organisation. We want the very best for emerging Europe, nothing more, nothing less. Your support will help us continue to spread the word about this amazing region.

Source: Emerging Europe