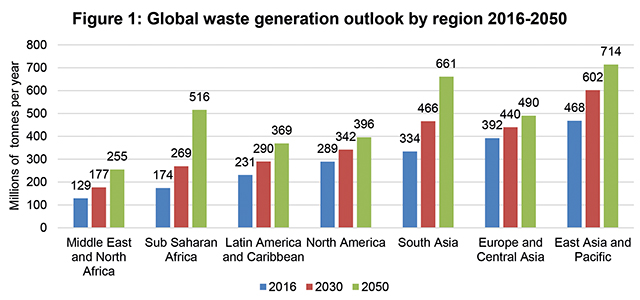

As waste accumulation keeps expanding, it increasingly poses a serious threat to human health and the environment. Waste can be the source of many diseases, it emits large amounts of methane (a potent greenhouse gas), and exacerbates global warming. According to World Bank estimates, without urgent intervention, the current levels of global waste will increase by 70% by 2050.

Proper management can substantially mitigate the issues associated with waste. When discussing optimal waste management, it is necessary to categorize the forms of waste and address each type separately. Within literature, one can encounter various categories of waste, for instance minerals, plastics, bottles, paper, or e-waste, while another key category of waste is biodegradable, so-called organic waste, which is simply a natural type of biodegradable refuse that is derived from either plants or animals. It is worth mentioning that 44% of the total global waste comes from organic materials (World Bank, 2018).

According to World Bank estimates, developing countries from East Asia and the Pacific, as well as South Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa, are the largest contributors to the production of organic waste. This is unsurprising, as, within their assessment, low-income countries are found to be the highest generators of organic waste: in 2016, 57% of organic waste was generated by low-income countries. This number is even higher in Georgia, where researchers estimate that organic materials make up 60% of total waste (Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 2020).

ORGANIC WASTE MANAGEMENT IN GEORGIA

In Georgia, there is currently no systemic approach that accounts for accumulated waste or an analysis of waste by type. Moreover, there are no large-scale waste separation systems, and different types of waste are discarded together in landfills. Nevertheless, in certain Georgian regions, waste separation and recycling do exist, with mostly paper, plastic, glass, and wheels being recycled. Notably, the greatest part of recycling is from paper waste. The Waste Management Strategy of Georgia (2016-2030) aims for the country to have a fully functional waste separation system by 2025, and to recycle 80% of paper, glass, and plastic and 90% of metal by 2030. These are extremely ambitious targets, some of which are even higher than those set by the European Union. However, the strategy has not set any goals for organic waste recycling.

According to the current waste management policy in Georgia, organic waste should be conserved in landfills. Organic materials typically decompose quickly and, once broken down by bacteria, create landfill gas (LFG), which is composed of several gases – methane, carbon dioxide, and a small amount of non-methane organic compounds. The problem is that these gases are dangerous to ecosystems, potentially causing both groundwater and air pollution, which also impact the climate.

Based on limited available data, the research suggests that LFG emissions from major landfills in Georgia will amount to 418.26 million tons of CO2 equivalent by 2030 (National SEA Pilot Project Team, 2015). The same research argues that if the Georgian government uses certain mitigation tactics, such as collecting and burning gas, emission levels could decrease to the CO2 equivalent of 291.76 million tons by 2030.

Considering the current pace of global warming, every country ought to fully attempt to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Nevertheless, despite the vast share of organic waste, there is no active policy in Georgia directly concerned with organic waste management or landfill gas mitigation issues (Heinrich Böll Stiftung, 2020). Due to the notable proportion of organic waste, it is even more important to develop an optimal organic waste management policy for Georgia.

WIDELY ACCEPTED APPROACHES FOR RECYCLING ORGANIC WASTE

One way to address the issue is to move away from the classical formula of make, use, dispose of, towards the development of a circular economy that aims to recover waste for future use from as many resources as possible. This is supported by current scientific advances, which make it possible to recycle or transform waste at minimum cost. Scientists have developed several methods to manage organic waste, and in this blog, we introduce the two most widely internationally accepted approaches and that could be adapted in Georgia.

Composting – Composting is a natural biological process, carried out under controlled conditions, which utilizes naturally present microorganisms in organic matter and soil to decompose raw materials. During composting, various microorganisms, including bacteria and fungi, break down organic waste into simple substances. Compost itself is a humus-like material that can be simply and harmlessly handled, stored, and used as a valuable soil conditioner, and used to improve the quality of soil. Though it is necessary to separate waste for composting, as not all types of waste can be used, for instance chemically treated wood products. Using organic waste for composting also helps save significant space in the landfills, as well as reduce the methane and greenhouse gas emissions ordinarily derived from organic waste.

Biogas – Biogas from food waste has a high biomethane production, potentially due to its organic matter content, thus it can be used to generate renewable heat and electricity instead of fossil fuels. Using organic waste for biogas production is considered to be one of the most power-efficient, energy-saving, and environmentally friendly ways of producing vehicle biofuel. Globally, China, the United States, Thailand, India, and Canada share the lead in biogas production, and international experience reveals that the world is leaning towards biogas.

POTENTIAL SOLUTIONS FOR GEORGIA

Although the aforementioned approaches towards organic waste may bring potential environment and economic benefits, they are also associated with drawbacks and implementation constraints. Biogas production, for example, is inefficient in areas where waste is not segregated and all forms of garbage are dumped together. In Georgia, there is no waste segregation in landfills, therefore using this approach would be technically unfeasible at present. Secondly, biogas production depends highly on the climate, with the process being most efficient at temperatures over 15 degrees Celsius. As such, biogas generation would need extra energy requirements to be functional in winter, which might not be economically viable.

Composting is a relatively easy technique for handling organic waste. The initial cost for implementing this policy is also relatively small. Utilizing compost bins, individuals and businesses can immediately start composting without further investment. Given that compost is a good substitute for chemical fertilizers, thus inducing decreased costs for agricultural production, it could be economically beneficial for farmers to consider composting. Moreover, compost enriches soil in the long-term by retaining water and air. For example, the existing literature suggests that a one percent increase in organic soil matter helps hold 20,000 more gallons of water per acre (Bhadha, 2018).

Given the present challenges related to waste separation, as well as the limited availability of financial resources, encouraging composting appears the most appropriate policy option for the country.

However, it should be noted, for a developing country like Georgia, that the successful implementation of any policy will require efforts to raise public awareness, define appropriate legislation, garner strong technical support, and acquire adequate funding. Public awareness, participation, and positive attitudes toward waste collection and source-level segregation play vital roles in the managing of municipal waste. It is therefore essential that the public is fully informed about the existing scale of the problem, expected threats, planned policies, and their potential role in creating sustainable waste management systems. It is especially important to raise public awareness regarding the need for waste separation, as some of the most efficient waste management approaches cannot be adopted without the disaggregation of different types of waste. Accordingly, the government, alongside implementing their selected policy, should act in the interest of the education of its citizens and provide all the relevant information.

By Mariam Chachava, Mariam Gogotchuri, Shota Katamadze, and Irakli Jgarkava