Hunger in the classrooms is on the rise in Georgia. Every child deserves to get a fulfilling education and exercise the right to adequate nutrition. The Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC) recognizes that all children up to 18 years of age are human beings in their own right, and as such are entitled to inalienable rights inherent to human dignity, including the right to healthy food and adequate nutrition, the right to non-discrimination, and the right to consider their best interests in all matters that affect them. According to CRC Article 27, children and young people should be able to live in a way that helps them reach their full physical, mental, spiritual, moral, and social potential. However, despite the CRC being ratified in Georgia in 1989, the particular right to adequate food and nutrition remains as an unaddressed issue.

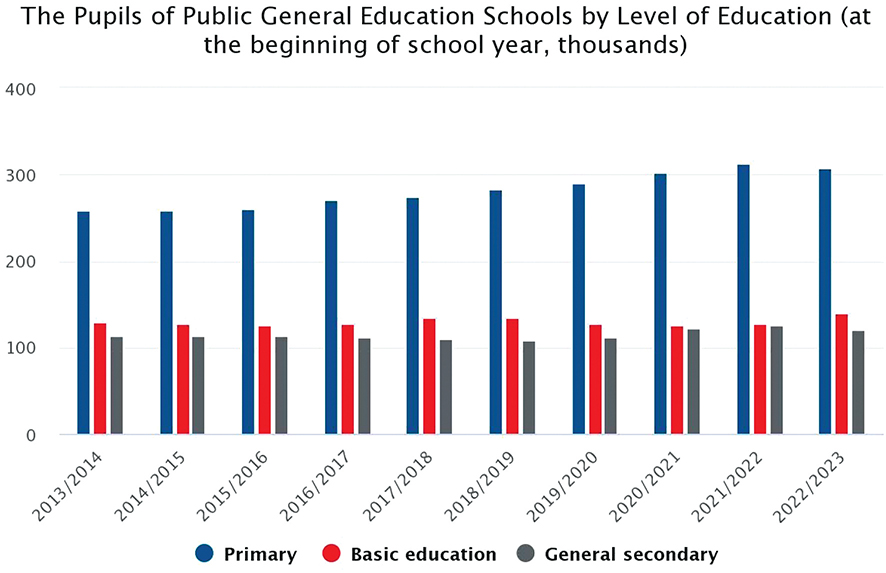

According to the National Statistics Agency, in 2020, 549,000 students were enrolled in public schools (see chart #1). A recent study surveyed 77% of the students and found that 42% of them have at least once gone hungry when attending classes, while 35% were “always hungry.” According to the estimates, 189,690 children (under the age of 18) are living below the poverty line.

In Georgia, children often arrive at school already hungry. This in turn is putting an extra burden on teachers, who are spending more time dealing with the effects of hunger in the classroom and less time teaching. Going without food in the morning has a direct impact on children’s behavior, as it lessens concentration. The issue worsened during the Covid-19 pandemic and since then the majority of the public school cafeterias have remained closed. It should be noted that even before the pandemic, the cafeterias at schools provided only simple snacks for teachers and students: There was no possibility to get nutritionally balanced meals even before the pandemic.

Yet, since 2008, the budget of the Ministry of Education has increased by 3.8 times from GEL 457 million to GEL 1.7 billion, and while this has had real results in terms of the quality of most children’s education in Georgia (Ministry of Education and Science in Georgia), the nutritional side remains unaddressed.

Addressing hunger among school children is an urgent issue that requires understanding the context at the local level, unlocking the political will, planning, and coordinating cross-sectoral cooperation. By acting collectively, Georgia can give every child the opportunity to create a healthy and vibrant future for themselves.

Georgian schools have no statutory obligation to provide meals, nor to ensure that students are sufficiently fed, not even socially disadvantaged students. Almost three-quarters of Georgian schools do not have cafeterias, forcing children to either bring food from home or purchase often low-quality food in shops or bakeries located nearby, often undermining children’s nutrition.

A child’s academic success is a key to their overall well-being. While in school, children learn not only academic material, but also social skills, knowledge about their health, and other essential life skills. Children gain more control of their futures when they are able to succeed in school. But there are certain factors that may hinder their ability to learn. When a child comes to school hungry, they may find it difficult to focus and get through the day. For some, once they finish their classes, they return home not knowing when they’ll get their next meal. The found effects count the following:

- Impaired focus

- Higher chance of repeating a grade in elementary school

- Impaired cognitive ability

- Language and motor skill difficulties

- Trouble adapting to the workforce as an adult

- Fatigue and stress

There have been some tentative steps taken to address this issue in Georgia. For instance, in 2015 the Minister of Labor, Health and Social Affairs approved non-binding national recommendations entitled ‘Healthy and Safe Nutrition at School’ which outlined school nutrition standards in detail and forbade the sale of snacks in schools. The document states that it is necessary to consume food from each of the four groups every day: 1) fruits and vegetables, 2) grains and cereals, 3) milk and dairy or their substitutes, and 4) lean meat, poultry, fish, eggs, legumes, nuts, seeds. The document also describes healthy snacks, important minerals, vitamins, and relevant types of food, and lists the types of products or components that need to be minimized in school meals, such as fats, sugars, and salts.

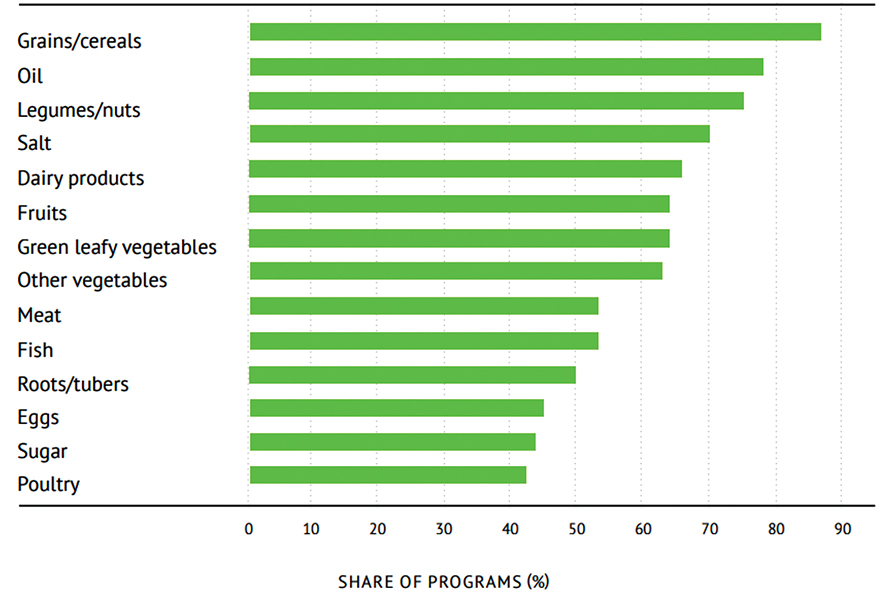

These recommendations have yet to be executed. Further, a report on the global survey of school meal programs in which Georgia participates (for no reason) publishes the products that are recommended to be included in school meals to ensure healthy and balanced meals at schools (see Chart #2).

Providing lunch at school for students is a common practice in developed countries. In the United States, the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) is one of the most effective approaches that a state can offer as social protection to students and parents, recognizing that malnutrition has detrimental effects on children’s development at an early age. NSLP is a government-assisted meal program operating in public schools for students, which provides nutritionally balanced, low-cost, or free lunches to children each school day. For example, in the UK, a typical school meal costs about £2 (GEL 8.6) and is usually paid for by a parent, in advance, online. The meal includes a main course containing fruits and vegetables, protein (for instance, meat, fish, cheese) and carbohydrates (for instance, rice, pasta), a dessert, and a drink. There are rules about how the food is prepared; for example, there are limits on the quantity of fried food. In addition, children are eligible for free school meals if their annual household income is below £7,400 (approximately GEL 32,000) excluding benefits, or if they receive certain welfare payments – a threshold, based on which more than one in five schoolchildren (1.7 million) in England were eligible for free meals in January 2021.

In Georgia meanwhile, children from socio-economically disadvantaged families are mostly left without food during the school day. In Georgia, it is estimated that it would cost 2,27 GEL (1 US Dollar) per student per meal, a cost of around 70,994.154 GEL per year. There are different models that can be developed to address this issue. The most feasible and cost-efficient is the means-tested approach which the UK implements – providing meal vouchers to disadvantaged families, while those that are not below the poverty threshold can get the same meal but the parent has to pay for it.

UNICEF Georgia has advocated for this issue, and some progress has been made in this regard. Namely, in 2022, in partnership with Parliament and the Ministry of Education, Science and Agriculture, a commitment for the School Nutrition Program was secured through: Assessing the situation; developing school nutrition standards; developing training courses for school managers; and carrying out a feasibility study in one region. However, no tangible results have been achieved so far. Despite international organizations such as UNICEF advocating this issue in Georgia, there has not even been a pilot program tested.

The proposed meal programs address the three main pillars: education, health and nutrition inequality, and agriculture. It is crucially important the national government prioritizes this issue and provides necessary support to ensure provision of nutritional meals in public schools.

The Ministry of Education, along with other actors in the process, should develop an action plan (2023-2025) based on the UNICEF-proposed model which creates a sustainable model that employs a multisectoral approach.

Launch a pilot program which will help them to elaborate the program before it is launched throughout Georgia.

Start with centralized administration of the program and then delegate it to the municipalities. Provide respective guidelines and recommendations along with technical support as needed.

Provide capacity-building and technical training to the school staff who will be responsible for administering the program.

Coordinate with other fields – non-profits, schools, and researchers. Ensure supply chain management – connecting farmers to schools.

Learn best practices from foreign countries that already have experience in successfully administering the program.

While hunger in schools remains a widespread issue, we must help combat this epidemic. These are some of the most important steps we individuals can take to help curb hunger both nationally and in the community, especially on the side of non-government organizations:

- Be an advocate for government programs by building awareness of childhood hunger and pinpointing tangible solutions.

- Support school programs as complementary to the national program. One option is to start breakfast clubs in schools.

- Local organizations can help schools launch and administer the program. Local non-governmental organizations can help schools administer the lunch programs and ensure their implementation. Often, non-government organizations have more capacity to ensure successful implementation of the program as opposed to national government employees and school staff.

It is proven that school meal programs work, and Georgia needs to make combating hunger in classrooms a priority!

Blog by Nino Jibuti