The contemporary spirit is filled with multicultural and universal concepts, which regard all cultures as being equal. In other words, we need to enrich our own culture, and respect its minorities. Historical background may be useful in supporting this global idea. Georgia appears to be a good example, as a permanent recipient of different ethnic groups and confessions, treating them moderately. Below we present one of the specific expressions of the idea.

Three-church basilicas present, indeed, a very special architectural appearance, and they are by and large concentrated in Georgia. These churches were built mostly in the 6th-7th cc. Who needed three separate chambers in a basilica, which thus restricted the space for the faithful? Christianity is a teaching, and a teaching needs an auditorium, and auditorium demands a large interior. Why, then, is the Georgian case so unusual? This paper deals with the problem of providing a functional explanation for the three-church basilica type.

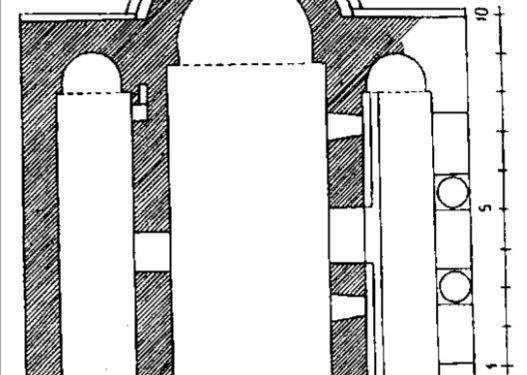

Lines of columns are present in a normal basilica, whereas a three-church basilica is formed when the columns are replaced by interior walls (see figure). The purpose of these interior walls is still obscure.

We remain inclined to think that Georgia’s Zaza Aleksidze was quite accurate in his conclusion, that those separated spaces in Georgia served for the different Christian confessions – Monophysite and Diophysite (Liber Epistolarum. Textum Armenicum cum Versione Georgica Edidit et Disputatione Commentariisque Instruxit Z. Aleksidze. Tbilisi. 1968, pp. 262-266). Indeed, there had been a substantial con¬fe¬ssional dualism in East Georgia (Iberia) in the 6th-7th cc. and those three-church basilicas could have served as an ar¬chitectural compromise for the sake of unity. And Iberia was a special case of this solution. An additional three-church basilica comes from Egypt (6th-7th cc.) and it is thought to be a Georgian origin (U. Morrenet de Villard. Una Chiesa di Tipo Georgiano nella Necropoli Tebana. Coptic Studies in Honor of Walter Ewing Crum. Boston. 1950, pp. 495-500).

In the 6th-7th cc., Iberia, being a traditional ally of Byzantium, was badly threatened by the Sassanids (from Iran) who made their attempt to build an Asian empire, and who demanded that the Caucasian range to be considered as the outer boundary of their political influence. Iranians supported Monophysites while the Georgians felt like to be Diophysites thus demonstrating their fidelity towards Byzantium and Europe. However, the lower classes mostly, inspired by Iranian aid and irritated by the local magnates, stressed their loyalty to the pro-Iranian branch of Christianity, as did some ambitious nobles. Moreover, the Armenian receptio (community) was present in Georgia and they were faithful Monophysites. The situation seems to have been even more complicated by the Iranian Zoroastrian proselytizing conducted either by the Persian receptio dwelling in the Iberian cities, or by new native converts to the Iranian confession.

Thus, Diophysites, Monophysites, and even Zoroastrians were present, and, in trying to maintain the national unity and social security of the country, one had to deal with them. What was to be done? Collect them in one place, ignore their confessional divisions, and not allow the appearance of truly separate, dominated by the Iranians, religious and political structures. The three-church basilicas were intended to serve this basic purpose, especially in the villages, where the serfs were rudely suppressed by their lords. Thus, although the village churches are very small, they are still divided into three sections. One could argue that there was no place for the Zoroastrians in a Christian church, but we must take into consideration the fact of Iranian (Sassanid) Zoroastrianism being largely influenced by European Mithraism, according to which even the date of birth of Mithras was fixed to the 25th of December (T. Dundua. Christianity and Mithraism. The Georgian Story. Tbilisi. 1999). The Armenians, inspired and strengthened by the support of Khusrau II, the Persian pro-Monophysite shah, accused the Georgians of disloyalty to the Monophysite faith, and of loyalty instead to all the Christian confessions, admitting even the Nestorians to the churches. Of course, the Georgians would have preferred their country to have been neatly Orthodox, but failing to achieve this comfortable situation, they tried to achieve a national, and not religious, unity putting all the confessions in one church (Liber Epistolarum. Textum Armenicum cum Versione Georgica Edidit et Disputatione Commentariisque Instruxit Z. Aleksidze, p. 191. Pope Gregorius I is said to have been delighted by the religious toleration of Georgia).

Europe faced the same problem earlier in the 4th-5th cc. with the Orthodox Christian folk, the Arians and the Mithra-worshippers living together. So, we are inclined to expect something similar there. Indeed, the joint basilicas or a Mithraeum inserted into a Christian church (Santa Maria Capua Vetere, Santa Prisca at Aventin Hill) could have served the same purpose.

The Egyptian case included three separate chambers, perhaps, with the Greek, Coptic and Armenian languages being involved in the church service. It is thought that a certain Cyrus from Iberia prolonged his activity founding the three-church basilica in Thebes in the 7th c. (Liber Epistolarum. Textum Armenicum cum Versione Georgica Edidit et Disputatione Commentariisque Instruxit Z. Aleksidze, pp. 167-272; G. Chubinashvili. Architecture of Kakheti. Tbilisi. 1959, p. 142 /in Russ./).

This pattern of confessional pluralism has continued to be precisely maintained. Being largely an Orthodox country, Georgia still embraced different communities, like as Jewish (from the 2nd c. B.C.), Muslim (from the 8th c.), Armenian, Roman Catholic etc.

Thus, a co-existence was easily achieved, which means that it can be achieved anytime, anywhere. Georgia is a good example of such co-existence, i.e. multiculturalism. The country has historically been prone to accepting different elements of different cultures which is well reflected in the skyline of the city. The cobbled streets of the older part (only 3 square km) of Tbilisi have synagogues, churches and a mosque.

The great Jewish synagogue on Kote Apkhazi street was built in 1895 by wealthy Jewish residents from the south Georgian city of Akhatsikhe. There is also a so-called “Ashkenazi Synagogue” likewise situated on Kote Aphkhazi street. There are also dozens of other small synagogues spread all over the city.

In Varketili district of the Georgian capital the Yazidi temple rises over the neighborhood. Built in 2015 it is one of the only three Yazidi temples in the world.

Tbilisi also boasts of having a fire temple, Ateshgah, situated in the older part of Tbilisi, just to the south of the fortress Narikala. Ateshgah, place of fire, was given a special status, that of national significance, later in 2007 elevating it to the status of cultural heritage.

Tbilisi’s multiculturalism is also evident in the fact that the city has a mosque where both Shia and Suni Muslims pray together. Located just below Narikala, the Juma Mosque was built by the Ottomans in 1720s to be destroyed by the Persian forces and again rebuilt and renovated on several occasions.

Not far from the Juma Mosque is located the Armenian St. Gevorg Cathedral. Believed to be built in 13th century, the cathedral serves as the Georgian Diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church.

Co-existence is a hallmark of Tbilisi. Its architecture reflects the multi-vector dimension of the capital city, its centrality in the geopolitics of the region and attempts of various powers to dominate Georgia.

By Prof. Dr. Tedo Dundua, Dr. Nino Silagadze, Dr. Emil Avdaliani, Ivane Javakhishvili Tbilisi State University