The World Health Organization’s declaration of Covid-19 as a pandemic on March 11, 2020 can be considered a watershed in the recent history of mankind. The pandemic and its concomitant changes, such as switching to remote activities, affected different aspects of our lives, including individuals’ participation in and behavior on the labor market. Georgia was no exception in this respect. The unprecedented nature of the crisis brought about unprecedented consequences for the country’s already vulnerable labor market. The unemployment rate deviated from its quite steadily decreasing trend and increased by 0.9 percentage points in 2020. Moreover, the labor force participation rate worsened from 51.8% to 50.5%, as the labor force shrank by more than 49 thousand individuals. Alarmingly, the change in female labor force participants was 48 thousand, or 98% of the overall change, which demonstrates one aspect of the inequitable impact of the crisis from a gender perspective. To better understand some of the other peculiarities of Covid-induced labor market effects, we looked at the last three quarters of 2020 and compared them to the same period in 2019. Here is what we found:

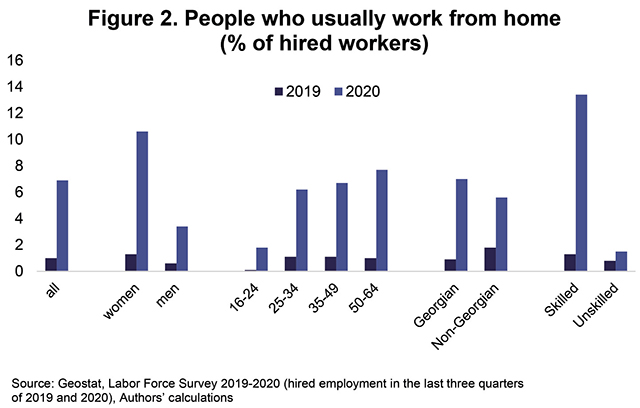

The proportion of individuals who report usually working from home increased by 5.9 percentage points and this change was largely driven by women and skilled workers.

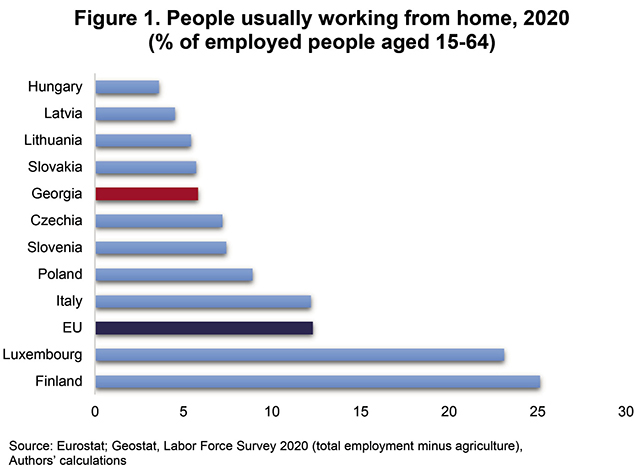

From the moment the first health threats were identified, the GoG started gradually imposing restrictive preventive measures, such as a curfew, a ban on public transportation, closure of schools and workplaces, and even a nationwide lockdown with the stringency index peaking in April 2020. Of course, these measures caused changes in work arrangements, as many jobs had to switch to an online mode. As a result, the data shows that the share of hired workers who reported usually working from home increased from 1% in 2019 to 6.9% in 2020. To put this number into context, according to Eurostat, the EU average for the share of hired employees usually working from home increased from 3.2% in 2019 to 10.8% in 2020 (note: EU figures take into account all four quarters of the given years). This puts Georgia far behind some developed economies, such as Finland and Luxembourg, but in close proximity with countries like Lithuania and Slovakia.

Interestingly, the change was driven mainly by women, among whom 10.6% reported usually working from home (compared to 1.3% in 2019) in contrast with only 3.4% of men (compared to 0.6% in 2019). This development is especially noteworthy in light of the following factors. First of all, there is an inherently unequal distribution of unpaid care work between men and women in Georgian households.

Secondly, the demand for unpaid care generally increased as a result of kindergarten/school closures, hindered paid care provision, and increased in-home, virus-related healthcare needs. Indeed, UN Women’s survey-based study showed that in the midst of the pandemic, around 42% of women reported spending more time on at least one extra domestic task as opposed to 35% of men. Taking these facts into consideration, it is quite intuitive to suggest that women who work from home are exposed to a heavier double burden in terms of employment and increased household chores levied on them at the same time.

Even more striking is the difference between skilled and unskilled workers. It is easily noticeable in figure 2 that a considerable share of skilled workers managed to adapt to the pandemic-induced reality by switching to remote working. On the other hand, unskilled workers, who constitute the majority of hired workers, were more vulnerable during the challenging times.

Hired individuals worked on average 2 hours less per week (on main and second jobs combined).

Covid-19 sharply curtailed economic activity and demand for labor, which is likely to have translated into a drop in working hours. Indeed, examining the weekly working hours of hired workers on main and second jobs combined shows a decrease from 46 hours in 2019 to 44 in 2020. The decreasing trend was almost universal across sectors, real estate activities being the only exception characterized with a 2 hour increase in average working hours. The most appreciable decrease was observed in the activities of households as employers, and accommodation and food service activities.

Overall, these findings are in line with worldwide trends. More precisely, according to the International Labor Organization, in 2020, an estimated 8.8% of total working hours were lost. Among these, half are due to the reduced hours of those who remained employed (and can be attributed to either shorter working hours or “zero” working hours under furlough schemes).

From a gender perspective, the drop in working hours was relatively steeper for men (50h to 47h) compared to women (42h to 41h). While comparing impacts for skilled and unskilled workers, we see no appreciable difference in the way the pandemic affected the two groups.

More people have to work part-time because they are unable to find full-time jobs.

In line with the decrease in working hours, the share of part-time employed individuals increased slightly (3.6% to 4.0%) in the economy as a whole. One might postulate that faced with Covid-induced difficulties, businesses had two possible solutions to decrease spending: first, laying off part-time workers (increasing the share of full-time employment), and second, replacing full-time employment with part-time (increasing the share of part-time workers). What we observe from the data is that the net result of these two effects is not universal across sectors. For instance, in the construction sector part-time employment increased from 1.1% to 2.3%, while for real estate activities it decreased from 5% to almost 0%.

In addition, there is an appreciable change in the underlying reasons behind part-time employment. More precisely, in 2020 71% of part-time employed individuals (compared to 58% in 2019) reported an inability to find full-time employment as the major reason they were not employed full-time. On the other hand, the share of individuals who did not want full-time employment decreased from 24% to 12%. Finally, there is a somewhat noticeable increase in the share of women who named housekeeping or looking after a sick or disabled person as a reason for part-time employment (5% in 2019 to 8% in 2020). This fact again highlights the particularly adverse effects of the pandemic on women.

Share of people working during evenings as well as during weekends decreased.

Again, in line with the overall decrease in workload, evening and weekend employment dropped considerably. One possible explanation behind this result could be the nature of the crisis which mostly affected tourism-related industries in which evening and weekend work is quite common. Indeed, looking more closely, it can be observed that evening employment decreased in arts, entertainment and recreation from 50% to 18%, similarly for wholesale and retail trade (51% to 36%) and accommodation and food service activities (77% to 49%). What is more interesting is that a similar trend can be observed in the construction sector in which evening work decreased from 48% to 21%. Finally, a decreasing trend in weekend employment is universal across sectors, with the arts, entertainment and recreation industry characterized by the steepest drop.

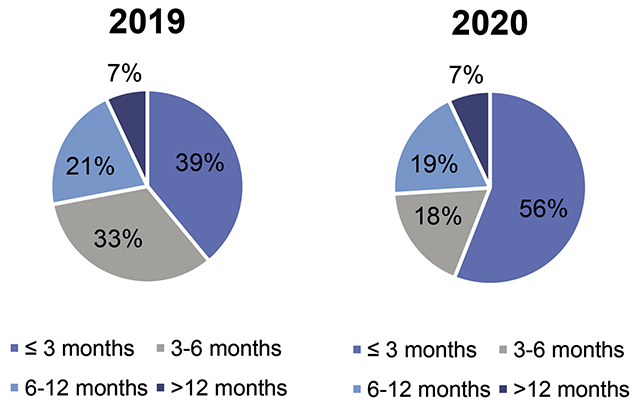

Businesses seem to have shifted towards much shorter-term employment contracts.

In 2019, the share of contracts with a duration of three months or less was 39%, while in 2020 this parameter increased to 56%. This phenomenon can be explained by the lack of predictability of the future due to the pandemic. By contrast, the share of contracts for more than 1 year, quite seldomly used in Georgia, remained almost unchanged (only 7 percent of all contracts are more than 12 months in duration).

SUMMARY

To conclude, as anticipated, the pandemic did affect the Georgian labor market through various channels: working arrangements changed, predictability decreased, and as a result of decreased economic activity, workloads were reduced. To make matters worse, some of these adverse effects were more pronounced for vulnerable parts of society: women and unskilled workers. Nevertheless, the full consequences of the crisis still remain to unfold as we have recently witnessed a record high toll for Covid-19 cases and as a response the government had to reintroduce some preventive measures.

By Mery Julakidze and Gocha Kardava of the ISET Policy Institute