The Eastern Partnership Index, developed by the Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum (EaP CSF), says civil society remains a force to be reckoned with across the EaP region, despite increasing challenges in Belarus and Azerbaijan, and plays an integral role in the EU enlargement process in Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine. It also says Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has catalyzed deeper integration between some EaP countries and the EU in transport, energy, and trade.

The EaP Index serves as a beacon, evaluating the progress made by the six EaP countries under three dimensions: Democracy, good governance, and the rule of law; Policy convergence with the EU, and Sustainable Development Goals. It targets EU and EaP stakeholders, policymakers, media and civil society.

The EAP Index goes beyond simply collecting and measuring data. It takes into account different forms of change (reform progress, advancement, retreat from democracy, policy deviations), as well as stagnation and lack of change. It integrates cross-cutting issues across its evaluation, with a keen focus on gender equality and human rights.

Moldova and Ukraine secured the top two places in the 2023 EaP Index, which acknowledges their achievements in meeting EU reform goals and accelerating their alignment with the EU despite very difficult circumstances. The 2023 EaP Index indicates that the two EU candidate countries are steadily making the kinds of systemic changes that Brussels expects them to do to proceed along the accession path.

Moldova’s top spot is attributed to its impressive performance on election-related reforms, political pluralism, the fight against corruption and equal opportunities, which gave the country an edge over the second-best performer (Ukraine).

Ukraine’s score was dampened by the war and the limitations on public life imposed by Martial Law since 22 February 2022. At the same time, the war has not eroded Ukraine’s will to reform, says the Index. The areas in which Ukraine progressed the most include independent media, freedom of opinion and expression and freedom of assembly and association, independent judiciary, and the fight against corruption. The war’s effect on Ukraine’s EaP Index score is seen most vividly in state accountability, the weakening of which is a direct result of Martial Law.

However, the EaP Index also says that approximation with the EU is a dynamic process and can easily regress when domestic or external circumstances change or simply if reform fatigue sets in. “Accordingly, Moldova and Ukraine’s rising level of approximation is ‘work in progress’ and crucially, many recent reforms, especially to do with elections, anti-corruption and constitutional reforms, have yet to be fully road-tested,” says the Index.

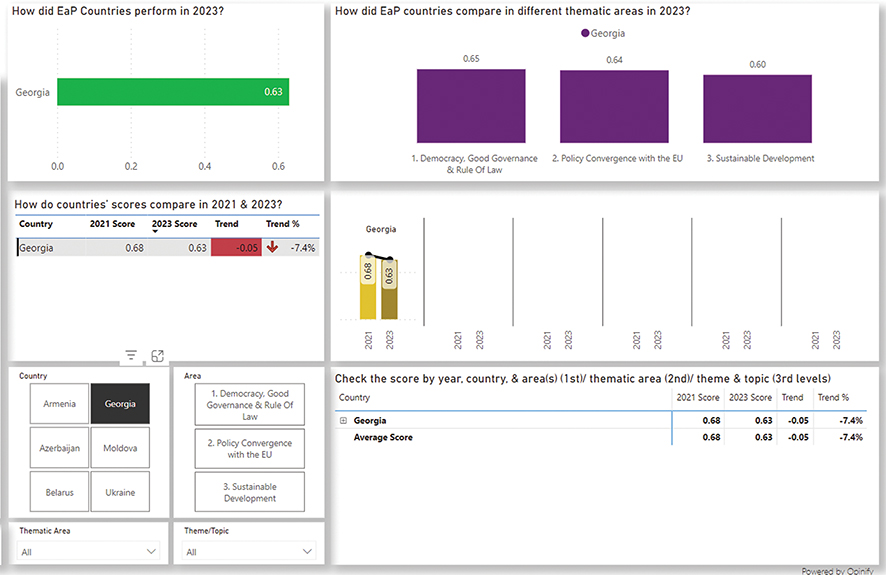

According to the study, Georgia’s performance was characterized by a “significant downwards drift, if not a sharp plunge in many areas which reflects the country’s political polarization”. Significant decreases occurred in democratic rights, elections and political pluralism, the fight against corruption, human rights protection mechanisms, state accountability, independent media, public administration, market economy, freedom, security and justice, and environment and climate policy, with the exception of freedom of assembly.

Armenia remained relatively stable in the 2023 Index, but reform stasis and potential for backsliding in key spheres is apparent. Armenia’s lower aggregate score is linked to slippage in democracy and good governance, especially state accountability, independent media (where it was previously the top scorer), freedom of opinion and expression and freedom of assembly and association and the fight against corruption, but these losses were ‘compensated’ by improvements in judicial independence.

Azerbaijan, says the Index, continues to edge towards “ever stronger authoritarianism and disavowal of independent civil society and media,” which is reflected in its diminishing scores in state accountability, freedom of opinion and expression and freedom of assembly and association and the fight against corruption. “A closer inspection of policies and practices in Azerbaijan shows very clearly that the country is at variance with all EU norms to do with democracy and good governance without exception.”

“Belarus continues to fulfil its designated role of Europe’s last dictatorship and does it well,” says the study. Virtually all residual elements of independent civil society and opposition have been extinguished, which is reflected in the country’s EaP Index score. The most notable downturn in Belarus’ performance includes state accountability, which reflects the growth of presidential power and rule by decree. In the areas where the Index recorded improvements in rapprochement with the EU, such as human rights and protection against torture or democratic rights, elections and political pluralism in Belarus, the reality differs from the legislation, which the authorities twist to promote the interests of the ruling regime and banish dissent (just as in Azerbaijan). Belarus’ dealignment with the EU on market economy and energy is an outcome of Minsk’s intensifying dependence on Russia and the application of Western sanctions.