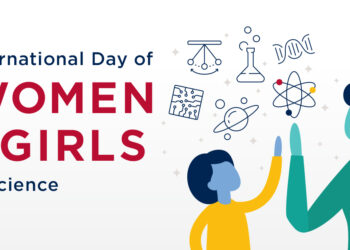

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) database, in just 2019, 5,220 people were estimated to have died due to air pollution in Georgia. In other words, according to such estimates, there are 130.6 ambient air pollution-related fatalities per 100,000 Georgians annually – a significantly higher number than most western European countries, and even higher than Armenia and Azerbaijan in the region (Figure 1).

AIR POLLUTION – COUNTRY OUTLOOK

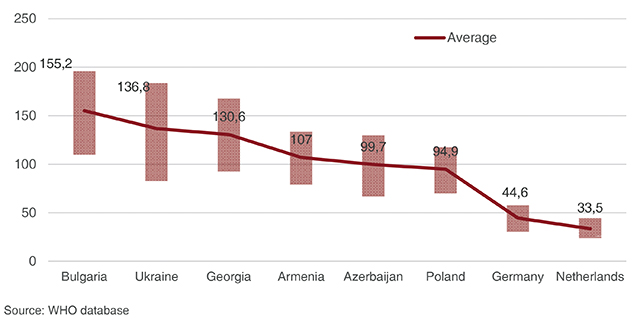

According to the Center on Emission Inventories and Projections (EMEP), around 82% of Georgia’s total particulate matter (PM) emissions derive from the industry and energy sectors (mainly wood consumption for heating) (Figure 2). Agriculture was responsible for emitting 86% of ammonia, industry caused 95% sulfur oxide emissions, while 93% of carbon monoxide emissions came from the transportation and energy sectors. Thus, policymakers should pay special attention to these notable sectors.

Compared to other European countries, Georgia has significantly worse indoor and outdoor air pollution (World Bank, 2020). On a yearly average, particulate matter concentrations are greater than those deemed safe for human health. Respiratory diseases associated with air pollution are also increasing in urban areas because of emissions in cities.

AIR POLLUTION IN TBILISI

Economic growth and rising income levels are likely to urge people in rural areas to transfer to safer fuels for cooking and heating, and to improve indoor air quality. Nevertheless, the problem of outdoor air pollution cannot be self-correcting, at least in the short term. Rather immediate increases in economic activity and rising car ownership are expected to cause greater air pollution in Georgian cities until the trend reverses.1 Looking at the growth dynamics of the number of vehicles in Georgia, the trend is linear and upward-sloping: Car ownership has been constantly increasing, by approximately 70,000-80,000 units per year.2 Notably, data from Geostat also highlights that only 7% of the vehicles owned in 2021 were hybrid or electric (significantly, the growth rate of the share of hybrid/electric vehicles in the total is decreasing).

As another contributing factor, the Georgian population is distributed unevenly, with most people living in the capital (approximately 60% in 2022, according to Geostat data). Notably, around one-third of all vehicles are owned by the population of Tbilisi.

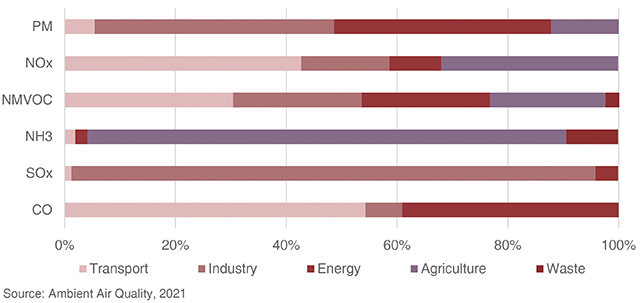

Pollution from vehicles is not the only source of air pollution in Tbilisi. The industry sector also egregiously contributes to total emissions throughout the city.3 Tbilisi typically dominates most economic and non-economic parameters among the cities of Georgia, thus, the fact that it is the most polluted city in Georgia hardly comes as a surprise. The data on air pollutants in Tbilisi shows that pollution has increased continuously over the last three years (Figure 3). In 2020, there was a significant drop because of Covid-19; with lower traffic and limited operation of factories there were reduced emission levels in that period. Nevertheless, one cannot claim that there is a significant downward trend.

POLICIES IN PLACE

The Government of Georgia has actively been working to improve air quality control in Georgia. The policies implemented in recent years include regulating the emission of hazardous substances from the industry, transportation, and construction sectors, a focus on urban planning, and promoting green spaces in urban areas.

The regulation of industry-released emissions includes instructions regarding the control of potential accidents at industrial sites and the procedures firms must go through during accidents to minimize the emission of hazardous into the atmosphere.4 In July 2018, the Government of Georgia introduced the air quality standard, which determines the target levels for different atmospheric substances. The ordinance also identifies that information on air quality should be publicly available in the form of an annual report.

Moreover, information about the concentration of pollutants in the air should be updated, at least daily, and if possible, in some regions, even hourly.5

Multiple steps were also introduced to reduce vehicle-induced emissions. The first step towards reducing such emissions was the fuel quality control mechanism. Within this mechanism, the sulfuric content in petrol and diesel decreased by 25 times and six times, respectively (from 2012 to 2017 and from 2012 to 2019, respectively). Since 2017, Georgia has used Euro 5 standard petrol. Furthermore, in 2018 there was no trace of lead detected in numerous gasoline samples.6 Since 2016, the policy has also tried incentivizing consumers to switch to modern electric or hybrid vehicles. Namely, the excise tax on hybrid cars less than six years old more than halved, while the same tax on old fuel-combustion vehicles doubled or even tripled (depending on the car’s age). The tariff on the import of electric vehicles was also reduced to zero. As a result, the import of hybrid cars increased by 20 times in 2018 compared to 2015.

Furthermore, in 2017, the excise tax on petrol imports doubled, and diesel almost tripled. Consequently, petrol and diesel fuel consumption reduced by 10% in 2017.7 Finally, in 2018, a modern, effective, and mandatory periodic roadworthiness testing system for all categories of vehicles was introduced and implemented to reduce hazardous emissions from older vehicles.

POLICY CHALLENGES AND THE NEED FOR URGENT SOLUTIONS

Despite various policies, including air quality plans in several big cities, the country still needs to reach its targeted pollution levels, which necessitates additional policy measures. From simple anecdotal evidence, it becomes clear that the technical inspection enforcement mechanism still needs to be revised.

Furthermore, as highlighted, the share of electric and hybrid cars in the total fleet is still negligible, while the trend for car ownership keeps increasing. Therefore, urban transport policies and practices play a critical role in incentivizing the reverse of increasing car ownership and helping switch to municipal transport.

Alongside car ownership, the booming construction sector has also been replacing green spaces, contributing to increasing dust levels in the atmosphere.8 Moreover, the Russian invasion of Ukraine in part redirected the Asian trade route to Georgia, thus increasing road traffic and the emissions from diesel-fueled trucks (Leijen, 2022).

Thus, first and foremost, technical inspections must be adequately enforced, and the rules should become more stringent. At the same time, the necessary infrastructure for electric vehicles should be implemented, in a timely manner, to incentivize their use. Furthermore, policymakers should pay special attention to the development of green public transport to decrease the popularity of private car ownership and reduce traffic jam-induced air pollution.

Besides which, residential buildings should not substitute green spaces, instead they should be widely incorporated into their construction. Policymakers should also impose, and follow, more stringent regulations for construction-induced air pollution and ensure the provision of more green spaces for citizens.

Additionally, if road transit increases throughout the country, the authorities should demand either air pollution filters for cars or install emission absorbers across highways.

Beyond these factors, it is essential to increase awareness among people about the severity of the topic. This would encourage them to take social responsibility for air pollution and require policymakers to press for more radical policy changes.

Finally, it is of utmost importance that the country develops a green growth strategy that incorporates air quality issues and helps Georgia comply with the European standards of living, thereby creating a safe environment for future generations.

CONCLUSION

International and local research has demonstrated how air pollution can impact human health drastically. Furthermore, a preliminary analysis has shown that the number of Georgian policies to combat air pollution and avoid pollution-induced diseases and fatalities are insufficient to reverse negative trends.

Notably, economic growth, without considering the green growth agenda, would in fact worsen the situation. Therefore, preventive measures, both societally and from policymakers, should be taken simultaneously to avoid fatal consequences.

1 The environmental Kuznets curve hypothesis suggests that environmental pollution increases at the beginning of economic growth. However, economic growth allows environmental remediation when it passes a certain income level.

2 Info.police.ge

3 Metallurgical industries, mineral industries, toxic waste management, chemical industries, food industries, storage and distribution of oil and oil products, etc. Source: https://air.gov.ge/

4 https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/1119518?publication=0

5 https://matsne.gov.ge/ka/document/view/4277611?publication=0

6 https://air.gov.ge/en/pages/4/6?news_event_id=1

7 Air Quality Portal.

8 Residential Real Estate in Tbilisi, 2022.

By Erekle Shubitidze, Guram Lobzhanidze, Mariam Tsulukidze