First published on Investor.ge.

As the first almond blossoms unfurl, Georgia’s tens of thousands of nut farmers are beginning to assess what income they made in 2023 and their chances for 2024. The nuts industry – hazelnuts, walnuts, almonds, and pistachios – is crucial for Georgia, being one of its largest in terms of exports, employment, and small-plot owner involvement; yet, it seems beset with challenges on every front. But with support from a wide range of schemes by government, donors, and large commercial groups, it is growing and holding its own.

At street level, new almond consumer products are now proliferating in Georgia, particularly from Udabno, the country’s largest almond producer and part of the Adjara Group. This is triggering increased consumer interest – its Vera shop sells almond flour, sweets, biscuits, nuts, oil, and butters all made from harvests on its 2,300 hectare Kakheti organic farm. International confectionery companies have introduced many new nut brands, and local efforts are being made to come up with new variants of Georgia’s traditional churchkhela.

Economically in Georgia, this industry has become a very active sector, expanding against a background of rising international demand for nuts as healthy, nutrient-rich food products – the nut market is currently valued at $46 billion globally and growing by around 6% a year, according to U.S. analysts Precedence Research. New companies are entering the Georgian market, diversifying the industry from the traditionally dominant hazelnuts by planting almonds and walnuts. Today, almonds cover 6,000 hectares, says Eastfruit, the East Europe and Asia horticulture market intelligence website, and the figure for walnuts is put at around 8,700 hectares, compared to around 70,000 hectares for hazelnuts.

Backed by state support, Georgia has been heavily investing in walnut production since 2015, with the government’s “Plant the Future” program data putting the total it has spent since then at $27 million. The Almond & Walnut Producer Association of Georgia is forecasting that walnut farms participating in the government program will produce an unprecedented 40,000 tons a year by 2025, 500% higher than post-2014 peaks in production.

Globally, almonds and walnuts are the most popular nuts, accounting for 27% and 22% of world nut production, respectively, in the latest crop year, with walnuts showing the fastest growth rate at 9%, according to the International Nut and Dried Fruit Council. China was the world’s dominant walnut producer at 53%, but the U.S. was by far the largest exporter (43% against China’s 15%, with most going to the EU). For almonds, the U.S. continued to be the global supply leader (76% in the latest crop year, with 47% going to Europe and 37% to Asia), followed by Australia (10%) and Spain (4%). And almonds were the most popular nut among consumers, at 31% against walnuts’ 19%.

Almonds’ rising international popularity and its forecast market price recovery (having halved over the last five years) are the reasons for increasing numbers of entrants to Georgian almond farming. Commenting on the latest season’s record international sales, global food commodity price data and market intelligence group Mintec says: “The sales are going to price-sensitive markets – India and China. A lot of this demand is driven by low pricing. The expectation from the market is that this trend is going to continue. Everyone’s expecting record shipments.”

Georgian production

Eastfruit names as major investors in almonds in Georgia as first Udabno; then Nuts Incorporated (800 hectares out of its total territory of 3,000 hectares, with exports planned at 500 tons); Nuts Cultivation (900 hectares owned by one of India’s leading niche restaurateurs and a global entrepreneur, Ashish Kapur, who is also aiming to export); Almond Co. (200 hectares, looking at the Turkish and Russian markets); Almond Tree (200 hectares and another would-be exporter); Mkisa (40 hectares and planning to become a service provider for developing and implementing self-sustaining green energy orchards).

Local production of almonds is rising rapidly: it was 2,000 – 2,500 tons in Georgia’s 2022-2023 season, and the Georgian Walnut & Almond Association has a production forecast of “over 14,000 tons by 2027,” Exports last season totalled over 150 tons, raising $280,000, with kernels going to the United Arab Emirates and those in shell to Uzbekistan.

Almonds start to fruit when the tree is two years old, though nuts do not appear in large numbers until it is five or six. By contrast, walnuts will not start to fruit before five years. So, says Anna Kevkhishvili, a board member of Georgia’s Association of Almond and Walnut Producers and founder of the family Kvemo Kartli walnut producer Anigozi, 2023’s large increase in the Georgian walnut harvest came as a result of planting in 2018. Fortunately, the bumper harvest coincided with a large increase in local demand, and equally fortunately, as she commented, there are now sufficient companies providing “the critical drying and processing…that will ensure the success of the development of the industry in Georgia.”

While the walnut producers are aiming at the EU market, they understand, Eastfruit comments, that “Georgia is not yet known on the EU market as a walnut producer. Therefore, it takes time to establish oneself.” But one advantage that might help Georgia is that its walnut crop is several weeks earlier than that in the U.S., a major EU supplier. Trial deliveries of Georgian walnuts have been made to Dubai, too, and India is another possible market.

However, for now there is also the growing home market, notes Eastfruit, as rising domestic demand is opening up import substitution opportunities in walnuts and almonds. Eastfruit points to increased local demand, particularly at supermarkets, and suggests this is due to the influx of Russians. Georgian walnut farmers, says Eastfruit, were able to sell their produce quickly last season, although the lower-priced imports held down prices.

Imports of walnuts, according to Eastfruit, more than doubled in the last crop year, with 1,850 tons coming in from Ukraine, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Turkey, Chile, and China. Imports of almonds Eastfruit puts at 1,300 tons, up 97% compared to the previous year.

Hazelnuts

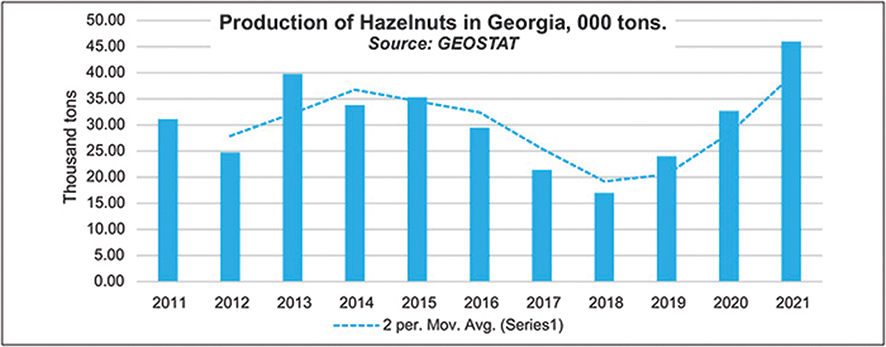

The size of Georgia’s hazelnut crop means it features on world production tables with a 3% market share. Turkey dominates the growing global hazelnut market, at 71% of production and 75% of exports, with the EU and UK the top destination.

While Georgia’s nut farming has traditionally been dominated by hazelnuts, this is beginning to change – particularly as hazelnut yields continue to be badly knocked by stink-bug infestations and production is no longer as financially attractive as it was fifteen years ago, says a 2022 annual report by the USAID Georgian Hazelnut Improvement Project. Despite price recovery since the slump of 2017-2018, this is being offset as inputs such as mechanization, pesticides, and fertilizers are becoming more expensive while not completely matched by government help and subsidies. Financial support to small hazelnut farmers in 2024 for the necessary agrochemicals and pesticides will total 29 million GEL, compared to 20.9 million GEL last year.

However, as Georgian Agriculture Minister Otar Shamugia pointed out in the summer of 2023, despite these obstacles, Georgia still exports to the EU over 70% of its production of hazelnuts, by far the largest amount from its nut farming. This is all the more impressive given the EU’s high level of regulated import controls, which Georgia still has trouble navigating.

Having risen at an average annual rate of 7.1% from 2016-2022, hazelnut harvests would, it had been hoped, be able to continue to grow last year. However, it was not to be. Heavy rain struck during the harvest and farmers had not been able to fully eradicate persistent stink bug infestations, so yields fell and the outcome was considerably less than expected.

Globally, modernization and new technology are being deployed to drive increased production in the nut industry, a trend which is also reflected in Georgia. This is particularly important for the beleaguered hazelnut sector because of the size of its production chain and thus its economic significance for Georgia. According to Eastfruit, this includes 75,000 hectares of plantations employing 70,000 farmers, staff at nine drying and storage warehouses, and 60 processing plants – 40 of which meet modern standards.

The Georgian Hazelnut Growers Association said last year that rather than increase orchard numbers, its top priority for the next few years was “to improve the quality of Georgian hazelnuts.” Problems listed by Merab Chitanava, chairman of the association’s executive board, at the annual conference were that: “The fight against the marble bug is not yet over, so producers must keep working hard. We plan to improve the average kernel yield to 47% (it is now 32%) and increase the yield…”

Modern commercial farms yield as much as 2.5-3.0 mt/ha, whereas Georgia’s national average is close to only 0.5 mt/ha. The low yields were mostly due to poor orchard management, but Merab Chitanava told international food sourcing and data hub Tridge.com that this could be rectified “even within two seasons.”

Modernization efforts and international assistance

There is now a wide range of assistance going into the hazelnut sector, helping to achieve the association’s aims. Already the number of border rejections of Georgian hazelnut shipments by the EU, most due to aflatoxins (a poisonous mold), is falling as post-harvest management of the nuts improves, notes Tridge.com. However, despite improvements in quality, Georgian hazelnuts are still getting prices below that of other major exporters – Turkish producers get around 10% more, but that country, with 71% of global production, enjoys huge economies of scale and relative efficiency.

Among the many projects supporting Georgia producers, most of whom have small household orchards with less than 2-3 hectares, is a two-year program from the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) that is helping 700 farmers (230 of whom are women). The plan is to go organic to gain higher prices and offer education on pest control, soil nutrition, grafting, and innovative growing techniques.

USAID has since 2015 been backing a hazelnut improvement project in Georgia, implemented by the U.S. food development organization Cultivating New Frontiers in Agriculture (CNFA) and working with major Italian confectionery group Ferrero Rocher (a very important player in Georgia’s hazelnut industry and the owner of 5,000 hectares of orchards). Activities have focused on increasing export sales and prices through improvements in quality, and enhancing Georgia’s reputation as a stable, reliable supplier of high-quality nuts.

One latest phase of the program is to build a traceability system, a key element to improve quality and consumer safety. But beyond this is a plan to improve the quality of data on Georgia’s hazelnut production as only then can full analyses be made of harvests and sales, as well as successes and failures. This, says the project’s last report, is vital “both at business and policy-making levels.”

By the Investor.ge Editorial Board