For an emerging market like Georgia’s, digital currency could promote financial inclusion and serve the ‘underbanked,’ or those living in areas where accessing commercial bank services is difficult

First published on Investor.ge

If your leisurely beachside reading this summer included news from the riveting world of central banking, you might very justifiably think the death of cash is nigh. Central banks around the world are diving down the blockchain-crypto rabbithole to catch up with the industry after years of nay-saying, tacitly admitting the future of money may just be on the blockchain.

China, the Bahamas and Sweden have already begun piloting central bank digital currencies (CBDC), while US Fed Chair Jay Powell announced over the summer that a digital dollar is ‘a top priority’ for the bank. The EU has also started formal research into a digital euro, and 80% of central banks worldwide are engaged in CBDC research, according to a recent survey by the Bank of International Settlements. Georgia even preceded the flurry of announcements with its own news in May that the National Bank of Georgia is working on a ‘digital lari.’

The reaction to the news has been tepid, with the media and public alike unsure of what to make of the endeavor. After all, you might say, ‘I’ve had digital lari since I’ve had online banking…’

What is digital currency?

Well, not exactly. Central banks currently only offer one direct form of money available to the general public – physical cash.

The money accessible in a mobile banking app is a type of private money secured by the commercial bank where it is kept. Central banks support and acknowledge this commercial bank money, which is why you can easily turn it into cash with a simple ATM withdrawal.

However, CBDCs represent a new type of money, directly linked between the central bank and the public that can be used for digital payments – essentially, a digital form of cash.

Like its paper colleague, the digital lari will be be a fiat currency, issued only by the National Bank of Georgia. Unlike cryptocurrencies, the value of which is often supported by proof of stake or proof of work concepts, a digital GEL will be controlled solely by the NBG, and offered at a 1:1 rate with its cash counterpart.

The National Bank of Georgia is still deciding on the exact structure of the digital currency, but it is strongly considering the use of blockchain technology, given its security and flexibility in programming.

Gains for consumers and the state

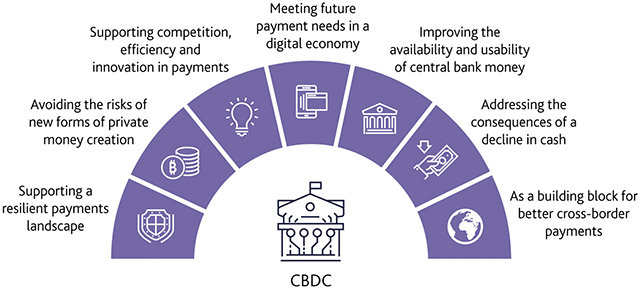

One of the primary purposes of introducing a CBDC is to create a quicker, more flexible and cashless settlement tool.

For everyday users, this will allow for the instant transfer of funds through a secure, national bank-backed platform, which may lower costs for consumers and businesses alike: cashless payments currently go through an intermediary, in most cases a bank, which takes a service commission. Be it paying for utilities, fines, or sulguni at the market, all cashless transactions have a commission. Georgian Fintech Association Chair David Kikvidze claims transfers in digital lari could save the economy “about 600-700 million GEL per year in service commissions. [And this extra amount freed up in public expenditure] could have a considerable effect on the consumer market,” Kikvidze says.

For an emerging market like Georgia’s, digital currency could promote financial inclusion and serve the ‘underbanked,’ or those living in areas where accessing commercial bank services is difficult. A currency linked directly to the central bank could ease the process through which social programs are distributed, lowering costs for the government and alleviating the burden some pensioners face when collecting their money at a brick and mortar bank. Adopting a digital lari could also make sending remittances easier, which accounted for 13.3% of Georgia’s GDP in 2020.

The National Bank of Georgia is still deciding on the exact structure of the digital currency, but it is strongly considering the use of blockchain technology, given its security and flexibility in programming

The NBG has even more to gain. Local currency loss of market transaction share through displacement by cryptocurrencies is one major concern that has central banks pursuing CDBCs. Rector at the Neuron Academy for Artificial Intelligence and researcher Levan Bodzashvili told Investor.ge that the NBG’s decision to pursue a CBDC is especially understandable given the country’s somewhat trying experience with runaway crypto-mining in the mid-2010s and the fact that its breakaway, Russian-occupied region of Abkhazia has now effectively become a playground for cryptomagnates.

“Cryptocurrency has decentralized financial resources in a number of states. A state’s financial power is concentrated in its national bank, which establishes the rules of the game, and the quick development of cryptocurrency could result in a state losing influence in this sphere. In order to stop this process somehow and wrest back the reins of financial control, central banks are looking at issuing digital currencies,” Bodzashvili explains.

Prodding consumers to pay more often with electronic means and by ensuring that cashless transactions remain within the realm of a centralized system could further clamp down on the shadow economy, the share of which in the total economy may be higher than 50%, an IMF Working Paper in 2018 estimated. In the long-term, the massive amounts of data generated by digital transactions formerly obscured by the anonymity of cash and cryptocurrency could better inform economic forecasting and policy making and equip the NBG to better enact appropriate monetary policy as well.

For the NBG, the cost of not implementing a CBDC could even prove detrimental to its monetary policy. The advent of easy-to-use digital euros and dollars with no Georgian equivalent could lead to a ‘digital dollarization,’ wherein the population would favor the use of digital foreign currencies and the central bank’s control would slip.

Head of the NBG’s Financial and Supervisory Technologies Development department, Otar Gorgodze, says that this fear of being eclipsed by competing digital currencies has been a large motivating factor for many central banks. Touching on Facebook’s announcement in 2019 that it intended to develop its own blockchain-based payment system, he notes “That’s probably why there was a big outcry when Libra [Ed. now Diem] was announced. It was suddenly recognized that it will be more global than any of the central banks’ currencies. And if it’s better and more efficient, then that would be it.”

But what about the banks?

One stakeholder that has expressed its take on CBDCs with less than fervent enthusiasm is the banking sector, which stands to lose market share as the traditional transaction intermediary.

President of the Banking Association of Georgia Alexandre Dzneladze says that in discussing the supposed benefits to be brought into the economy by a CBDC, “it is important for everyone’s interests in the process to be protected.” Dzneladze further told Investor.ge that it ‘would not be reasonable’ to fully replace bank transactions with digital lari, as this would inflict losses on commercial banks.

“We see a risk of certain commercial operations generally performed by the population with the help of banks going over to the digital lari, which is why it is important for us to know what preconditioned the adoption of a digital lari, as well as to talk about and review the details of what awaits commercial banks if it becomes possible to conduct financial transactions by bypassing them,” Dzneladze told Investor.ge.

In response, the National Bank says that their goal is not to weaken banks: they see digital lari not as a competitor to electronic bank transactions but as a more modern alternative to cash. While the NBG’s Gorgodze notes that their CBDC does hope to lighten some of the financial burden that small businesses face with commission fees, he is also insistent that this new form of currency will not be possible without the assistance of the private sector and commercial banks:

“The digital lari will not replace banking services or the need for an intermediary. Besides, the digital lari can become a new possibility for banks and financial companies to offer new products to consumers. For example, there will be wallet providers, license providers, maybe a payment service provider which has customers. They can onboard this network and customers. The private sector will be responsible for this process. We decided to go with a private-public partnership to the maximum.”

Another issue that has worried banks has been that of savings, and whether consumers will be tempted to keep their money in the NBG’s digital account as opposed to in commercial banks.

“For this, we will have a direct limit on wallets, how much you can hold in them. In Europe, they’re considering limiting it to around 50,000 euros. Here, we will consider an amount that the average Georgian needs for transactions…the digital lari won’t be for saving,” says Gorgodze.

Yet others ask the question: to what extent will the National Bank of Georgia and other state agencies have access to information about consumer transactions?

As concerns day-to-day transactions, Gorgodze says, “We’re thinking about a setup that is very much like banks. In this network, which is operated by the central bank or somebody they trust, there is no personal information tied to transactions themselves. You’re not visible on this network, only your bank knows that this is your account and you’re transacting.”

In other cases concerning financial crimes such as money laundering, or in cases where transactions may be tied to terrorism, Gorgodze says that the state will have to go through a legal process to receive access to detailed information.

The National Bank of Georgia has invited financial institutions as well as technological and fintech companies to participate in the development of the digital currency, hoping to eliminate regulatory, financial, and technological problems through joint cooperation.

The USAID Economic Security Program has been offering technical assistance to the NBG, advising on functionalities of CBDCs and helping to build solid linkages with major fintech players who can provide valuable inputs for the development of the CBDC project.

Program lead George Darchia explains that “our role is to provide technical advice and explain to major players like fintech, financial institutions, e-commerce and other vendors what the digital lari is, to make sure they understand it and [can] make a decision as to whether they want to utilize it or not.”

In addition to clarifying the national bank’s intentions, Darchia’s team will serve in an advisory role for both the NBG and “private sector representatives, who, at the second stage, will be even more involved in the consultative process to define what are the best functionalities and most appropriate shapes of CBDC for Georgia.”

Through active communication and consultation with major market players, Darchia is confident that the process will be inclusive enough to reflect the views of private sector actors significantly.

The exact date of the launch of the digital lari remains under wraps, and the NBG has yet to release a time window on the project. However, speculation has it that potential pilot projects may be seen as early as summer 2022. Cash won’t be dead by then – you’ll probably still be using it at your next beachside vacation to pay for lounge chairs – but it may already be on the way out.

By Ani Mezvrishvili for Investor.ge