We began our conversation with Merab Kopaleishvili by discussing his impressions of his latest exhibition—a milestone moment in his career. Recently, Merab made his debut in the Parisian art scene with his works showcased at the prestigious Asia Now art fair, one of the key highlights of Paris Modern Art Week.

Held annually in October, this renowned event attracts art enthusiasts and industry professionals from around the world. His participation was made possible through a collaboration between Gallery 4710 and Reach Art Visual, which provided curatorial support and guidance. Merab’s works were displayed alongside pieces by two other renowned Georgian artists, Tamar Nadiradze and Merab Gugunashvili.

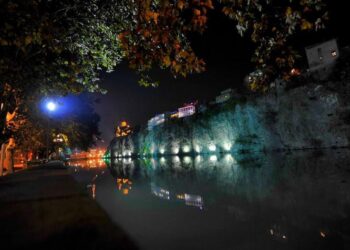

“Paris? How could anyone possibly say anything bad about Paris? Especially an artist? But to be honest, I wasn’t exactly spoiled by exhibitions before this,” Kopaleishvili tells us. “One day, as I was sitting and sketching, I got an unexpected call. They said, ‘You need to fly to Paris.’ Two days later, there I was, with my work in tow. As Hemingway said, Paris is a ‘moveable feast’ that stays with you for the rest of your life. It has this rich cultural tradition—a kind of ark that has gathered strands of modern culture from all over the world. Georgians were part of that story, too. Together, artists from all corners have built what we now call the ‘Parisian School.’ Each person has contributed their part, like adding their own stone to the grand structure of culture and world heritage. And when you add your own little pebble—no matter how small—it fills you with a sense of pride, a pleasant warmth inside.”

“I had read so much about Paris growing up, and when I finally walked its streets and visited its museums, everything felt oddly familiar. Every street, every painting, felt like an old friend. I had first encountered these masterpieces in books when I was 12, but seeing the originals in person is an entirely different experience. You notice the brushstrokes, the cracks in the canvas—it feels alive. Take Veronese’s The Wedding at Cana, for example—the largest canvas in the Louvre. I’ve known that painting since childhood, but standing before it in person? It was surreal. It’s more than just a painting; it feels like an opera, with Verdi’s music filling the air and the characters singing their parts. Paris has a personal story for everyone, and I have mine too.

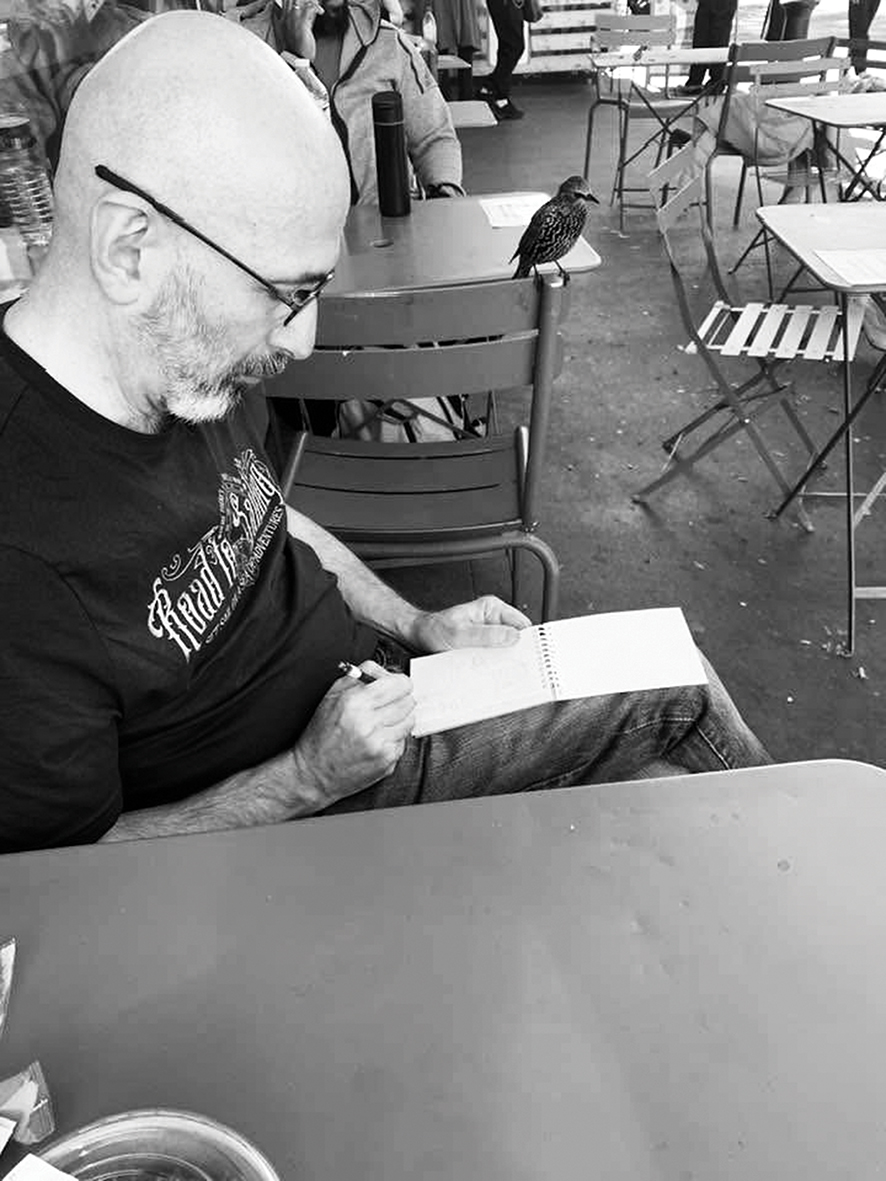

“The next day, Paris felt like mine—I’d domesticated it, so to speak. I walked the streets, explored as if I had always lived there. I’d seen it all in books, on TV, and in reproductions, but standing in front of the originals gave me a whole new experience. As an artist, it added layers to what I already knew. These impressions and feelings are now a big part of my work. I even brought back an album of sketches from Paris. What I thought would be a fleeting moment of inspiration turned into a whole series, which I think will evolve into a complete cycle of Parisian travels.”

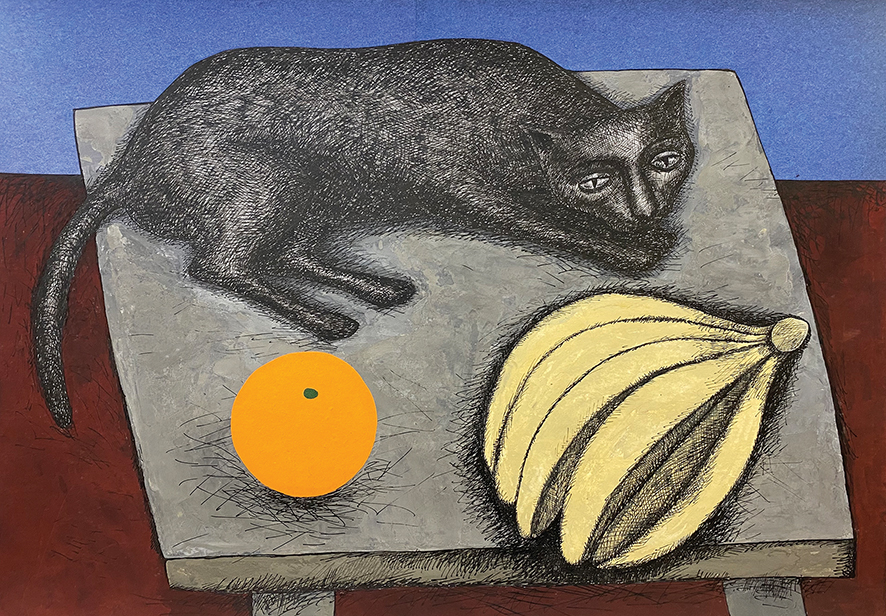

Your works reflect the influence of Georgian traditions of expression and visual culture, while also intersecting with European modernist painting and beyond. How would you compare your art to the pieces exhibited in Paris, and where do you see it fitting within such a diverse visual and cultural kaleidoscope?

There’s a unique genetic code that runs through your bones and flesh—something that cannot be erased or changed, no matter what. It might add something to you, just like a shell attaches to the bottom of a ship, but the ship itself remains unchanged. This genetic code stays with us across generations. So, it’s entirely possible that an artist from the early 20th century and one from today could channel the same idea, despite the difference in time.

At the exhibition, there were artists from all over the world, each with their own unique perspective, their own personal struggles, their distinct characters and visions. It was like seeing someone’s childhood imagination come to life—the creatures they’ve invented, maybe something they dreamt up when they were young. For instance, there was an artist from Japan who shared fragments of his distant childhood, offering a glimpse of his world. It was a reminder that experience, in all its forms, shapes how we see the world.

Art isn’t like sports where you compete for an Olympic gold medal. It’s not about who’s better than whom. Instead, it’s simply another color being added to the vast canvas of world culture. And the beauty of culture is that it has no boundaries. It’s not that one culture starts here and ends there—it’s all interconnected, and each part nourishes the other.

What do you think Georgian artists bring to the global art scene?

You know, Georgian art has always found itself in a unique position—right at the crossroads of European and Asian cultures. And it’s fascinating because all these different influences don’t compete with each other; they actually enhance and complement one another. Our deep roots in Hellenistic culture, the way we’re connected to it and carry it forward, is something that feels very natural to me. It’s inseparable from what it means to be Georgian. Despite everything—centuries of war, changes in fortune, and so on—that connection has never really been broken. It’s like, no matter what you do, you’re part of it. Even if you try to push it away, you can’t really escape it. You can’t change your blood. That’s why, consciously or unconsciously, your work always reflects what you’ve been raised with, what you’ve grown up around. It comes from childhood memories, from those early experiences.

When you think about it, we’re all connected to generations of ancestors who shaped who we are. They’ve passed down their essence, their history, bit by bit, and that’s embedded in your very DNA. That’s what fuels creativity. You keep creating, keep experimenting, and then, one day, something meaningful just comes out. But here’s the thing: how much of that is really “Georgian”? When you’re an artist, there’s this supranational feeling that you can’t ignore. Art, like color or music, doesn’t need translation—it’s universal. It goes beyond borders. But even as you explore different influences, something of your roots always remains with you. No matter how far you go or how much you evolve, you’re still a Georgian artist at heart. Your temperament, your climate, your mood—everything that makes you who you are, it’s all reflected in your work.

The more Georgians exhibit abroad, the more we introduce our culture to the world, and that’s invaluable—especially since we have so much to share. I’m truly grateful to Reach Art Visuals for organizing the exhibition in Paris. Their work made it possible for us to showcase our art on such an important international stage.

Creating something truly new and powerful must be challenging. How do you navigate the process and find your way forward?

Indeed, it is hard to create something significant after The Angel of Kintsvisi was painted. I mean, Galaktion used to walk these streets. How do you create something after that? But, I think that’s the thing with art—it’s not about one painting following the next. It’s about the process, about walking in the dark, not knowing exactly what you’ll come across. That’s what the creative journey feels like. Sometimes, it’s like you’re feeling your way through, and it’s a bit uncertain. But even when it feels like you’re lost, you trust your craft. You trust in your own process.

So you think it’s more about the journey than the outcome?

Absolutely. The process is everything. There’s always that moment of uncertainty, that little agony of thinking, “Maybe this is where it all falls apart.” But it never does. As a professional, you have a foundation, something that helps you stay grounded and focused, but there’s always this feeling of searching. It’s like a constant crisis—but that’s what keeps art alive, right? It’s always in this perpetual cycle of rebirth, constantly evolving. And I think that’s the mission of humanity, really: culture. It’s not about the end result, the finished work. It’s about the path you take to get there. A city might be destroyed, but in its ruins, they’ll still find remnants of its culture—artifacts, poems, paintings. That’s what matters. It’s not about where you end up; it’s about the journey. And as long as you have the strength, you just keep going.

By Team GT