In the world of architecture, where space meets imagination and structure becomes emotion, Shorena Tsilosani stands out as one of Georgia’s most consistent and forward-thinking professionals. A lecturer at the University of Georgia and head of her own architectural studio, Tsilosani combines decades of design and spatial-planning experience with a passion for mentoring the next generation of architects.

“Architecture is not only about aesthetics,” she says. “It’s about understanding how space communicates with people — how it feels, functions, and inspires.”

With more than twenty years of experience, Tsilosani has worked on numerous landmark projects — from early infrastructure designs to large-scale contemporary concepts. Among her notable works is the architectural transformation of the Pabellon Hotel in Kakheti-Kvareli, a project that perfectly reflects her philosophy of harmony between the natural landscape and functional design.

In this conversation, she shares insights from her multifaceted career — spanning teaching, design management, and complex spatial projects — while reflecting on the mentors, students, and principles that continue to shape her path.

You’ve been lecturing for several years now. Tell us about your teaching experience and what drives you as an educator.

I’ve been teaching architecture, interior design, and spatial composition at the University of Georgia for eight years. My goal has always been to share the knowledge and experience I’ve gained through practice. When I stand before my students, I don’t just teach design — I try to teach perspective.

Architecture is about how space interacts with people. My aim is to guide students toward becoming professionals who think creatively, act responsibly, and stay inspired.

Let’s go back to the beginning of your career. How did your professional path start?

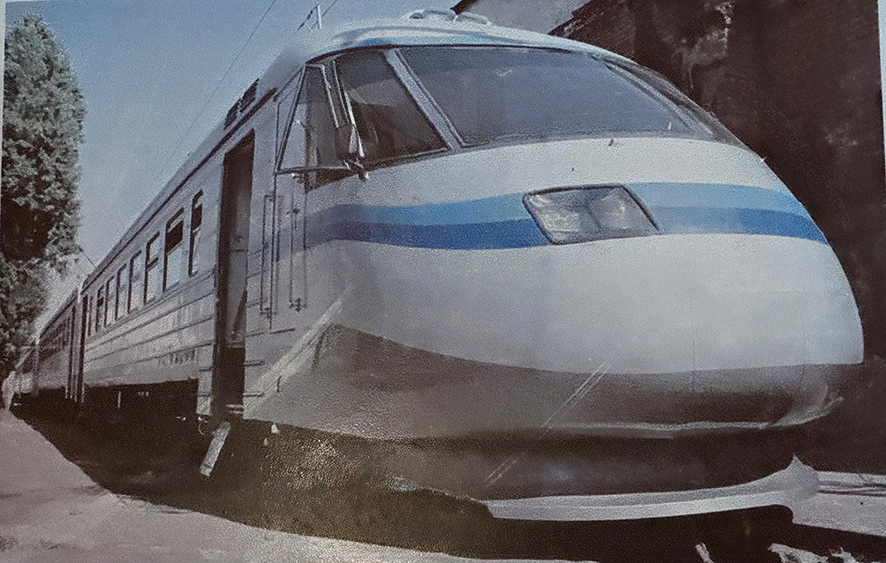

Shortly after graduation, I joined the team designing Georgia’s first high-speed train in the late 1990s. I was only nineteen or twenty, and found myself leading a small design group at the Wagon Repair Factory. It was a challenging time for the country, but we were united by the belief that design could help Georgia move forward.

We weren’t only drawing — we were managing engineers, programmers, and new computer-aided systems unfamiliar to most back then. That experience taught me early on that architecture isn’t just creativity; it’s leadership, coordination, and teamwork. Looking back, it was my first encounter with what

I later recognized as design management — understanding every technical detail, uniting different specialists, and ensuring the project met international standards. That lesson has stayed with me throughout my career.

You often emphasize mentorship and guidance. Who were the mentors that shaped your path?

I was fortunate to have remarkable mentors who helped me find my voice. Among them were the late Irakli Tsitsishvili and Tina Chichua, who inspired independent thinking. Lado Vardosanidze who was my MDA mentor. But perhaps the greatest influence came from Professor Shota Bostanashvili, who once told my instructors, “Don’t teach this girl to draw lines — help her develop her ideas.” That moment defined my approach to creativity.

My family also encouraged me from a young age, taking me to exhibitions and meetings with architects. When I first entered the Academy of Architecture, I immediately knew I had found my place. Since then, being an architect, engineer, and lifelong learner has remained my greatest joy.

Architecture is such a diverse field. How do you define its main directions and the architect’s role within them?

Architecture encompasses spatial and urban planning, structural design, and the narrower field of design itself. In the past, an architect handled everything, but today’s projects are far too complex for one person. That’s why design management has become essential — it bridges creative and technical aspects, ensuring coherence across teams.

I first realized its importance while working on the Zhordania Clinic on Abashidze Street. Since I wasn’t a medical specialist, I began by interviewing doctors and learning how a clinic truly functions — from patient flow to environmental requirements. That research became the project’s backbone. Today, that’s precisely what design managers do: translate a client’s needs into an architectural and technical language everyone understands.

You also worked on a fascinating project in Avlabari, one of Tbilisi’s oldest neighborhoods. What made it special?

That project taught me what it means to treat a city with respect. Avlabari carries centuries of history, and I felt deeply that my design must follow its rhythm rather than impose mine. To ensure historical accuracy, I collaborated with Mr. Giorgi Chanishvili, an exceptional professional and now a close friend.

He discovered old photographs of the site — once a military garrison and stable — and even wrote an architectural text describing its original essence. Inspired by his writing, I created fifteen conceptual sketches, translating his text into visual form. The collaboration reminded me of my professor’s words: “Text is architecture.” Every design must tell a story and speak in harmony with its surroundings.

That project was approved without objections and later used as an example for other architects. For me, it symbolized professional respect — when knowledge, history, and design work hand in hand.

You often connect architecture with text and meaning. What does that idea represent for you today?

My professors — Shota Bostanashvili and later Lado Vardosanidze — always told me: “Text is architecture.” It means that every structure should begin with an idea, a narrative, a meaning. Now, in the era of artificial intelligence, that philosophy has new relevance. I study programming and AI, not to change my profession, but to explore how technology can expand creativity. For me, it’s a luxury to dive deep into these systems and see how they can enhance imagination. Yet no matter how advanced technology becomes, architecture will always start with human thought — the invisible “text” that gives meaning to space.

One of your most notable recent projects is the “Pabellon” Hotel in Kakheti. How did that project take shape?

“Pabellon” was both a challenge and a revelation. The site was originally an industrial wine factory built to hold over a million bottles, located at the base of Kudigora Mountain near Ilia Lake and the Durudji River. Transforming that vast industrial structure into a warm, welcoming hotel required reimagining every aspect of its form and function.

We faced structural, environmental, and aesthetic challenges — from reworking the concrete shell to blending it naturally into the landscape. I wanted guests to feel part of the scenery, not separate from it.

Today, when you sit on the terrace, vineyards unfold before you and mountains rise behind — it gives you that timeless, “beyond the hills” feeling that connects architecture with emotion.

We also analyzed tourism patterns and visitor behavior. Tourists in Kakheti usually stay two or three days, so we designed spaces that invite them to linger: a wine-viewing gallery, terraces, and areas for festivals and family gatherings. “Pabellon” became more than a hotel; it became a living environment — a place where space tells a story.

Your studio has become a creative space not only for projects but also for learning. How do you engage with your students outside the university?

My architectural workshop has evolved into a platform where education and practice merge. Together with my former students — Mariam Svanidze and Luka Jalaghonia — we’ve built a community where young people can explore architecture hands-on. Students and even high-schoolers join us to learn, experiment, and develop their ideas.

They don’t just observe — they participate. I want them to experience how architecture breathes in real environments. Seeing their curiosity and enthusiasm reminds me why teaching is such an integral part of my life.

That’s a wonderful model. What roles do Mariam and Luka play in your studio?

Mariam has a rare talent for the conceptual and textual side of architecture — she understands the “language” behind every design. She coordinates research and communication with students. Luka brings technical precision — he specializes in programming and visualization, turning 2D drawings into realistic images that help clients see the final concept.

Together, we’ve created a mentoring chain: I share my knowledge with them, and they pass it on to the next generation. This continuity — the exchange of passion and expertise — is what keeps architecture alive.

What philosophy guides you as an architect and educator?

Architecture is about harmony — between people and space, imagination and function. When you design, you shape not only buildings but lives. That’s an enormous responsibility, much like a doctor’s, because your work affects how people feel, move, and connect.

As an educator, my mission is to help future architects see that every wall they draw and every space they imagine has meaning. If I can pass on that awareness, then I’ve done my job. Architecture is not only a profession — it’s a calling.

Mariam Svanidze, Shorena’s former student and current colleague: “My collaboration with Ms. Shorena began in 2021, when she was my lecturer at the University of Georgia. From the very first lecture, I was captivated — she was unlike any teacher I had met. She treats every student individually, almost intuitively understanding their inner potential. She helped us discover why we chose architecture and what we truly wanted to express through it.

“When I chose her as my diploma supervisor, she gave me the freedom to find my voice. She even arranged for me to work on a project at the Wagon Repair Factory to deepen my practical experience. Over time, we realized that my strength lies in research and the textual part of projects — the foundation that precedes design.

“Now, in our studio, I work as a junior mentor, consulting students on research and communication. Ms. Shorena has an incredible ability to identify young talents and guide them toward growth. With her, every day feels like learning something new.”

Luka Jalaghonia, Shorena’s former student and current colleague: “My journey with Ms. Shorena began almost by chance. I had heard from Mariam that she was an exceptional mentor who truly supported her students, so I chose her as my diploma advisor too. That decision changed everything — she guided and motivated us constantly.

“Imagine: in one semester, she supervised ten diploma projects, and all of them were defended successfully. Now, I work with her on programming and visualization — I transform 2D drawings into 3D images that help clients envision their future spaces.

“I feel incredibly lucky to have her as a mentor and now as a colleague. She creates an environment where growth never stops — where learning is part of everyday work.”

Interview by Ana Dumbadze