Interview by Nina Tsipuria

Even the risk of being an enemy of the communist regime didn’t stop Grit Seymour from becoming the first East German designer to have a show in Paris.

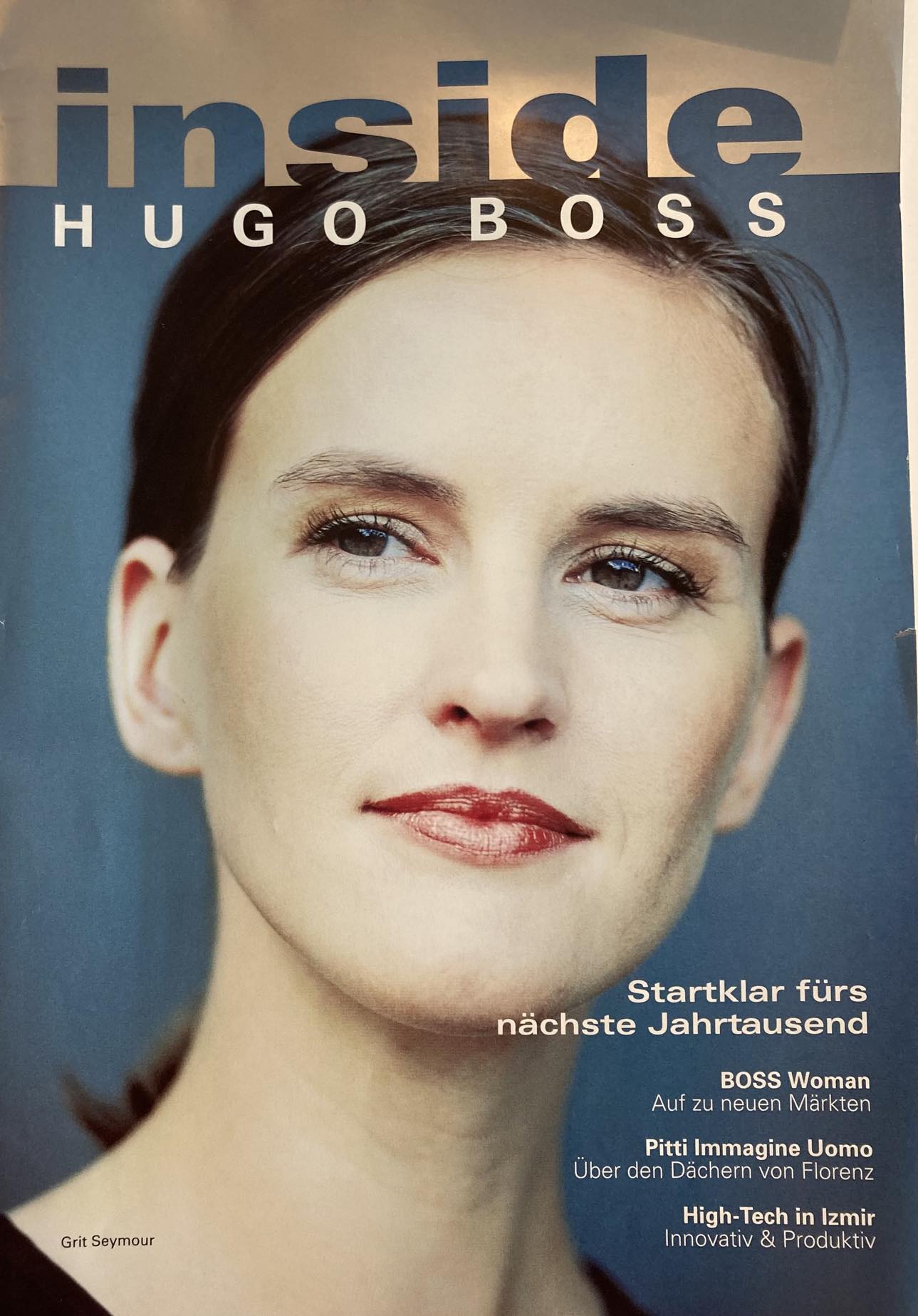

Grit Seymour is a former model, designer, and creative director for international fashion brands such as Max Mara, Donna Karan, Hugo Boss, and Wolford.

She has been passing on her knowledge of fashion to students since 2006, first for six years at the University of the Arts and since 2016 as a fashion professor at the HTW Berlin (Hochschule für Technik und Wirtschaft Berlin), where she initiated creative projects such as the design of the film costumes for the movie “In einem Land, das es nicht mehr gibt,” which features part of her life story.

Besides teaching design to her students, Grit also spreads her knowledge about sustainable fashion. Her career started in East Berlin, in the GDR, a country that no longer exists; however, the memories of the days spent there chasing her dreams and not giving up still remain.

She never gave up, despite the hard days when authorities expelled her from the university because of her political views. After leaving the GDR, Grit went to Central Saint Martin´s College of Art and Design in London and decided to complete her bachelor’s degree there. Then she moved to the Royal College of Art from 1992 to 1994, where she received a Master of Arts degree.

The author of Hugo Boss’s first women’s line has an exciting life story. I met Grit on a rainy day in Berlin, on Kurfürstendamm, the place where she first stepped when she left the GDR and felt the freedom of the West. Filled with memories, I honor Grit for sharing with me unbelievable stories about her life and career.

Dear Grit, did you live in the east part of Germany?

I was born in Halle (Saale), which is about 2 hours away from Berlin. When I was 18, I moved to West Berlin.

You wanted to become a doctor, just like your mother, but then you changed your mind. Was it difficult to be a designer in the GDR?

Everything was very strictly regimented. Only as many people could pursue higher education and apply to universities as there were jobs, so “no one could be jobless,” as it was said in East Germany. Only three people per year were allowed to study fashion design because there were only three jobs in the industry every year. There were a lot of factories producing for the local market, while some of them were also producing for the foreign market and exporting. East Germany was kind of a third-world country of production for some capitalist countries. There was a restricted number of fashion designers, and the government allocated only three new jobs per year for fashion designers.

And you were one of those three?

Yes. I took the entrance exam; however, for the first time, I didn’t get in. Everybody had to be a worker or peasant first, before you were allowed to study. When I applied the second time, I got my study place.

This was your dream at that time, right?

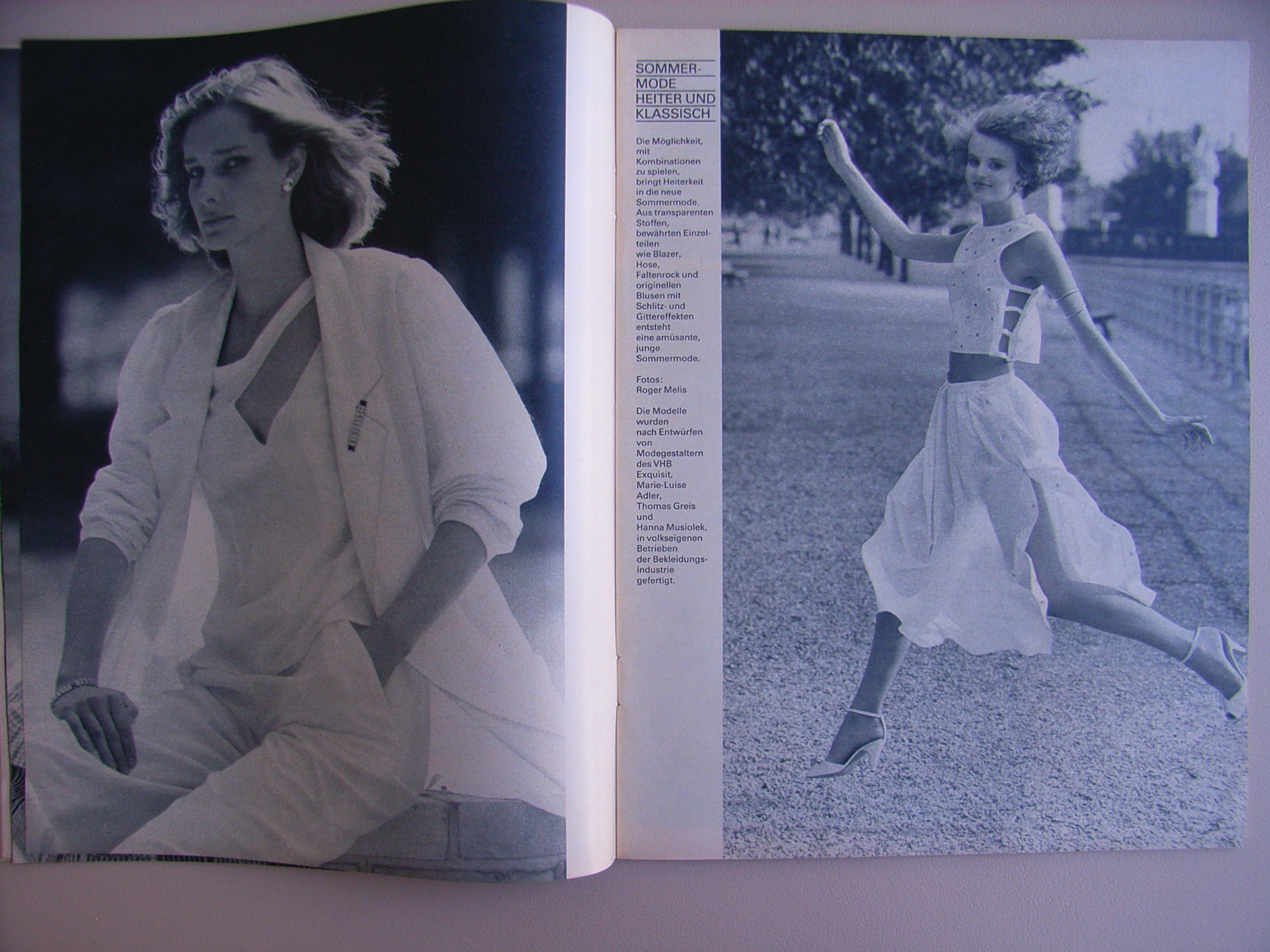

Yes, it was really a dream that came true. It was like, “Wow, I’m entering another world.” It was the only fashion college we had in East Germany, and it was linked to the one and only luxury brand of the GDR called Exquisit. The head of the fashion department at the college was also the head of Exquisit, and he was recruiting the best students to work for Exquisit. Thus, I was in line to get this position, which seemed to be the absolute dream job in East Germany. However, I only spent a short time at the college, because soon I was expelled due to political reasons. I was part of the political opposition movement called “Swords to Ploughshares”. A lot of people were gathering at the churches to protest communist parties. It was an underground movement. At some stage, many people from this group were sent to the west, and the East government thought that the problem was solved.

I met them in Czechoslovakia. On a return trip from Czechoslovakia, I was taken off the train. A record by Nina Hagen, a book by Max Frisch, one by Erich Fromm, and the magazine “Spiegel” were found by the Stasi in my bag. I had been under observation for some time. At school, I had been part of the movement “Swords to Ploughshares,” and I secretly met with my friends who had been expelled from the GDR. My school report said: “She does not show her positive attitude towards our state.”

This was the reason for expelling you from the college?

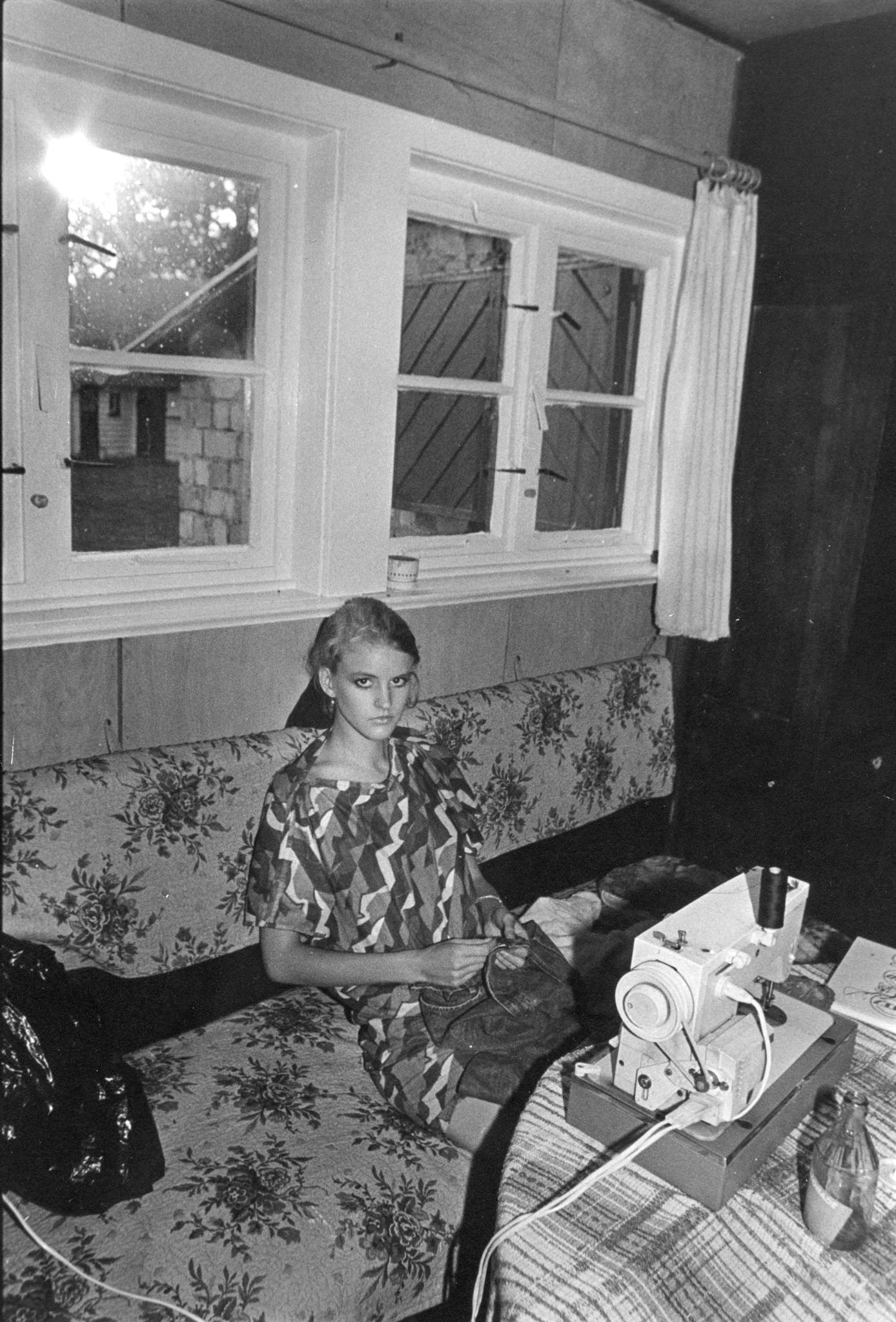

Yes, because of this situation, I was expelled from college and sent to the factory as a worker, as a seamstress, as a form of punishment. I was told that I had to prove that I changed my mind and became a “good citizen.” I was a bit rebellious; I was not supposed to go back to Berlin, as I was forbidden to go there, but I still went to Berlin on weekends and worked as a model for the fashion magazine “Sibylle”, while during the week I worked in the factory. I was 18–19 years old at that time. Eventually, the director of the factory saw me on the cover of the magazine, and he was really upset because I wasn’t supposed to be in Berlin. The Stasi (the state security service of East Germany from 1950 to 1990) warned me that if I wanted to continue my studies, I must have collaborated with them, but I refused. “Collaboration” meant to spy on my colleagues, on my family, and on my friends. I refused, so they told me, “Ok, you can stay and be a factory worker until the end of your life.” After that, I decided to leave the country, because I knew that there was no future for me. It took a very long time; it took 3 years to leave East Germany.

You left your family after three years of preparation?

It took three years to get permission to go to West Germany. Shortly after a few months, my mother also followed me. We reunited here in West Berlin.

What was the feeling when you moved to West Germany from East Germany?

It was the 16th of November, 8 PM. In East Berlin, we didn’t have much light in the streets; it was quite dark and gray. I actually came here on Kurfürstendamm, where we are now. I was like, “Wow, what’s happening here?” I was swamped by the colors and billboards at night. I called my mom, who was still in the east, and described everything. It was so overwhelming and like “dreams coming true”. The main feelings I had were freedom and relief. Finally, I could say what I was thinking; I could create my own life. I could travel, and nobody was watching me. When I arrived, I was interrogated by French, English, American, and German secret services; they thought I was a spy from the East. So, this was kind of strange for me to be interrogated again. Then I started studies in West Berlin and continued modeling, so I could finance my studies. After studying for my bachelor’s and master’s degrees in London, I went to Italy.

You’ve been the creative director of Hugo Boss, and you created their first women’s line. Before that, they had only a men’s line…

The Boss Women’s line was launched in Milan, and it was the biggest hit. We were about five people in the beginning, and half a year later we were 150—the design team, production team, commercial team, and PR team. I was head of the design department. Firstly, we had a test line to see how everything would work. Hugo Boss men’s wear was already very powerful on the market. The first line that we produced had a huge show in Milan and received very positive feedback. The inspiration came from Berlin in the 1920s and Marlene Dietrich. That line was for cool and feminine women.

You designed for Max Mara and Hugo Boss in Milan, Rena Lange in Munich, Donna Karan in New York, Daniel Hechter in Paris, and Wolford in Austria. Different countries, different cultures… Do you think about their culture during your work process, or just about commercial purposes?

Both. Let’s say that in Paris, I absorbed the Parisian feeling; then, of course, I took this and tried to export this feeling to the world.

You came out of the view of Parisians?

Yes, but one of the major markets is Germany; it is the biggest market in Europe. I guess people were interested in my German perspective. I really get into the culture, study it, and then create. In New York, Paris, and Milan, customers think differently and shop differently. In Paris, it seems like everybody really cares deeply about fashion, which is highly respected.

Do you visit those stores you have been creative director of?

Sometimes.

Do you like their collections now?

Sometimes yes, and sometimes no. My style was timeliness. I like feminine and timeless clothing.

What is timelessness in fashion?

Each favorite piece in your wardrobe. It’s a bit like the concept of Donna Karan’s 7 easy pieces that every woman should have in her wardrobe. Fashion is part of our culture. The industry got so crazy that when I started, we did two collections each year, and now it’s 12. There’s too much stuff on the market. The fashion industry is the second biggest polluter of the environment, straight after the petrol industry. As I’m teaching at the university, we are working with the students on more environmentally friendly solutions, for instance, take knit. This is a more environmentally friendly product because you don’t have to cut and throw the access material away. Also, there is the possibility to reknit or create something new out of an existing resource. There are also a lot of solutions like vintage, recycling, and upcycling, so I am promoting this direction.

I teach students not only about how the product will be but also about what will happen afterwards. There are two directions in fashion: mass market fashion, which is about launching a lot of collections that are worn or not worn and thrown away, which is really causing the problem; and on the other side, there is the direction of more sustainable thinking and a circular economy, which looks at fashion in a holistic way, including fair trade and how animals are treated. One of the most important things for me is what happens after the garment isn’t worn anymore. A garment will be worn for about 9 years: the first three years it’s up-to-date in fashion, the next three years it’s kind of ok for you to wear, and the last three years you might wear it in your garden. And then you shouldn’t throw it away; you can make something new from it. It can be composted or reworked, or new fabric can be made from it. There are many different possibilities; it’s important to think about it, and you shouldn’t throw it away because there are landfills full of thrown-away garments or they are burned and pollute the environment. That’s why fast fashion is a real problem.

What are the students most interested in nowadays?

Actually, today’s students are very political. They are interested in environmental matters, and they think about women’s rights and gender equality. It happens automatically; even if you try to avoid or ignore political news, people around you will still talk, and friends will discuss politics, so you are always influenced by the news.

Which is your favorite brand?

It’s hard to say. I’m more interested in future concepts, like what are new materials or what will really impact the industry and people’s lives, for instance—the invention of Lycra. [Author: By the mid-1970s, with the emergence of the women’s liberation movement, girdle sales began to drop as they came to be associated with anti-independence and emblematic of an era that was quickly passing away. In response, DuPont reimagined Lycra as the aerobic fitness movement emerged in the 1970s. The association of Lycra with fitness had been established at the 1968 Winter Olympic Games, when the French ski team wore Lycra garments to compete. This popularized the brand as essential athletic wear because of its flexible and lightweight material] Social and cultural movements change fashion. Such things really excite me.

At the end of our conversation, I’ll ask you about Georgia. You visited Georgia a few years ago…

When I visited Georgia, I recognized some of the atmosphere, it felt familiar to me, particularly to around the time when the wall came down. I had a similar feeling in Tbilisi to what we experienced in Berlin at that time: it was exciting, the start of fresh beginnings, full of potential, and a little frightening.

I enjoyed Georgia for that reason. I felt so connected to the people and to the atmosphere. I felt that Georgians act from the heart, and they are very friendly and open. The food was amazing. I love the aesthetics of Tbilisi. You can feel hope and optimism in the air. I saw really fashionable women in Tbilisi, a bit like in Paris.