Sanna Namin is a Swedish–Iranian multidisciplinary artist based in London. She works with sculpture, performance, and textiles, often exploring themes of identity, cultural belonging, and personal history through material and form. Her practice is hands-on and process-driven, using materials such as fabric, foam, and metal to create sculptural works that investigate the body, movement, and presence.

Sanna graduated from the Royal College of Art in 2023 and has exhibited her work in London, Stockholm, and Greece. She is currently participating in a three-week residency in Georgia with the Ria Keburia Foundation.

What is the main idea of this artwork?

This artwork is a response to what is currently happening in Iran. I am half Iranian and half Swedish, and I arrived in Georgia for my residency at the Ria Keburia Foundation just as protests began after the new year. From Kachreti, the straight-line distance to Namin, Ardabil—where my father’s family is from—is only 430 kilometers. This geographical closeness intensified my awareness of events that were already present and ongoing.

Over the past weeks, concern for people in Iran, including my own family, and admiration for the courage of those standing up to the regime have been constantly on my mind. I had wanted to make work about Iran for a long time but struggled with how to approach it. The current moment made it clear that I needed to respond through my work.

When I visited Tehran almost eleven years ago, I noticed a great deal of protest street art. It made me reflect on how visual language becomes a vital tool when speech is controlled. In Iran, anonymous street art is especially significant, as artists and musicians who challenge the regime risk imprisonment.

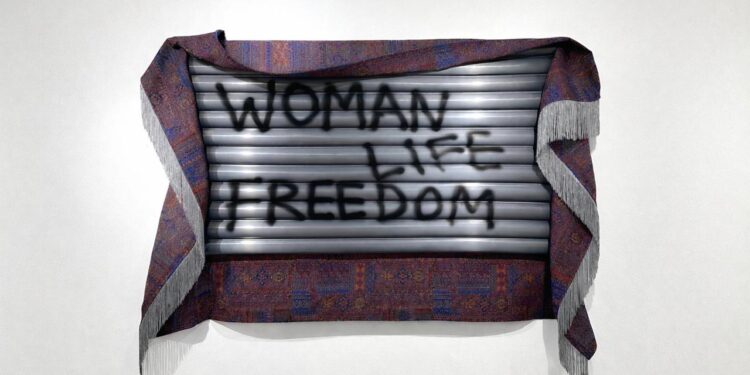

The tubes in the work resemble a shutter, referencing how closed and restricted life in Iran can be. The graffiti text “Woman Life Freedom” points to the most basic rights people are demanding. The Azerbaijani–Persian fabric found in Lilo Bazaar wraps the piece as a reminder that culture survives even when regimes attempt to erase it.

How does the phrase “Woman Life Freedom” change the emotional impact of the piece?

I want the artwork to feel urgent—something that cannot be ignored.

The phrase “Woman Life Freedom” is a reminder of what this revolution is about at its core: freedom. It draws attention to a struggle that has been ongoing since 1979 and is still not fully acknowledged. While people in Iran continue to resist, many media outlets remain silent, and world leaders have not done enough to respond.

The words insist on visibility and urgency. They name a revolution that is already in motion, even when it is ignored. “Woman Life Freedom” is not an abstract slogan; it is a direct demand for the most fundamental right: freedom. This work holds that reminder and refuses to let it disappear.

What are your future plans?

At the moment, my focus is on the present. When so much is happening in the world—especially in Iran—it feels impossible to separate the future from what is urgently unfolding now. I want to continue working through art as a way of responding to this moment and staying engaged.

Alongside my own practice, I work as a freelancer and as a tutor. I want to continue working in this way—developing my own projects while also supporting artists who have important things to say.

By: Sophio Dvalishvili